This article has its origins in my “One Hour/One Painting” sessions, an idea I developed a number of years ago to practice a different—and I hope a more profound and more rewarding—way of looking at art. I write about it in the hope that readers might wish to try it out for themselves or in the company of others, since I believe that learning to pay close attention to a work of art has the potential not only to change the way we visit a museum or a gallery, but also the way we live our lives.

This may sound like an immodest claim. But I have come to believe in recent years that we need only to open our eyes to see things clearly. This may seem obvious, but as I discovered, it is in fact no easy trick. A great many of us go through our lives without really looking at what is simply there, around us. We live in a state of confusion about who we are and where we are going, and we unquestioningly believe things about ourselves and the world that simply are not true. We choose to see through the smoked glass of ignorance, presumption or delusion. And we end up being fooled by what we imagine we see, rather than what is really there. “One Hour/One Painting” asks nothing more of those who join me than to slow down enough to sit and look at what is right there, in front of their very eyes.

Let me tell you how this came about. It started at a moment several years ago, when I was shocked, quite painfully, into the sudden awareness that I had been drifting my way through life without any clear sense of purpose or direction. I had reached, frankly, a state of rudderless confusion. I had allowed myself to be blown hither and yon, without knowing how to chart a course toward greater clarity—with the kind of attentiveness that would ask of me. Thankfully, my unwelcome but much needed wake-up call—the details are unimportant here, but it was one of those merciless, breath-snatching gut punches that life sometimes delivers!—arrived at the very moment I needed it, providing the trailhead to the path I have followed ever since. My earliest steps along that path were guided by the books I turned to at the time; for the first time I plunged into Ram Dass, whose Be Here Now I had been urged to read decades earlier but had dismissed as some kind of Eastern pseudo-religious cant that had nothing to do with the realities of my life. I suppose I was simply not ready for its wisdom.

Now I was eagerly reading not only Be Here Now but The Only Dance There Is, and as much of Ram Dass as I could lay my hands on. Then I happened upon Pema Chödrön’s When Things Fall Apart in a bookshop while vacationing for a few days in Ojai, California and devoured it hungrily, page by eye-opening page. At last I had begun to understand the value of living with clear eyes and an open mind. I learned how greatly I stood to improve my life—not to mention that of those around me—if I could only penetrate the fog that had obscured the way I had been looking out at the world. I began to understand how different life would be if I could just learn to see things clearly.

Despite my old habit of instinctive resistance to anything so slow and silent, I began to meditate. What I’d presumed to understand about the practice years before had led me to scoff at it as being something for people who were more “spiritual” than I—and I confess I did not mean that as a compliment! It was in any case, I judged, far outside my Western cultural heritage—as though I were a prisoner of my past. And finally, one of my false but firmly held beliefs assured me that I was incapable of the necessary mental discipline; my mind, I had always managed to convince myself, was so busily occupied with its familiar thoughts and worries that I’d be utterly unable to sit still and concentrate for two minutes, let alone a longer period. I could feign admiration for those who were so disciplined, but I was sure that meditation was not for me.

Such was my mind-set, then, when a friend who was sympathetic to my predicament persuaded me to suspend my disbelief for long enough to give his brand of Buddhism a try. It involved chanting, and it would, he insisted, not only solve my painful dilemma, it would change my life. He taught me the prescribed mantra (nam-myo-ho-renge-kyo) and instructed me to sit and chant it every day for increasing periods of time, having set a firm intention in advance as to what it was I needed. I could chant for anything, he told me, from release from my suffering to a new car, if such was my desire. So I began to chant—I have to say, with a good deal of initial skepticism. But I soon discovered that the magic actually did work, opening doors for me I never dreamed were there. I found new ways to cope with any adversity that came my way. And I persuaded myself that the practice was a fine way to “meditate” without having to worry about what was happening in my head; the repetition of the words was enough to keep the every-busy brain occupied.

Quite ignorant at the time about the many different forms of Buddhism, I learned only later that this particular practice, Soka Gakkai, was just one of them—and one that was regarded with some disapproval in more conventional Buddhist quarters. But it was my introduction, and I’m ever grateful to my friend for having put me onto it. The practice got me focused in a way I had never been before, and helped to lift me out of a particularly difficult period in my life. It also prepared the way for the silent, vipassana meditation practice that I have followed for now more than 15 years. Its basic principles offer sound guidance to anyone looking for success and fulfillment in life; you learn to show up, sit still, get focused, and persist.

So that’s one part of the story. The other part is also personal. It concerns my professional life as a writer. I started out as a poet and translator, but years ago I was introduced to the world of contemporary art and began to write about it. I wrote because I found myself looking at the work of artists that, at first, seemed strange and difficult, even off-putting, and writing has always been my way of coming to terms with what I don’t yet understand. In short order, the work of new, young, often experimental artists became the focus of my creative output. It took me a while to establish a reputation for this work, but by the time I hit upon the idea for my “One Hour/One Painting” sessions, I had already been publishing articles and critical reviews in national magazines for decades.

It was once I began to learn about the value of paying attention, then, that I began to take more careful note of how I was looking at art. It disturbed me more than a little to realize that I could easily walk into a show at a gallery or museum, take it all in—so I thought—speedily and efficiently with my discerning eye, and then go home and write about it. So it was disconcerting to catch myself, sometimes, spending more time with the wall label than with the painting I was going to write about. I was not alone. I observed others, most visitors, in fact, doing much the same. It’s a phenomenon described with wry amusement by Michael Kimmelman, the New York Times art writer, on the occasion of a visit to the Louvre in Paris. “A few game tourists,” he wrote:

glanced vainly in guidebooks or hopefully at wall labels, as if learning that one or another of these sculptures came from Papua New Guinea or Hawaii or the Archipelago of Santa Cruz, or that a work was three centuries old or maybe four might help them see what was, plain as day, just before them.

Almost nobody, over the course of that hour or two, paused before any object for as long as a full minute. Only a 17th-century wood sculpture of a copulating couple, from San Cristobal in the Solomon Islands, placed near an exit, caused several tourists to point, smile and snap a photo, but without really breaking stride.

It was of the coming-together of this life-change and this observation, then, that “One Hour/One Painting” was born. The notion was conceived quite soon after the experience of my first full hour of silent meditation. I had found out about a local Buddhist sangha that gathered for an hour’s sit each Sunday morning—something of which I would never have dreamed myself capable before, and now approached for the first time with a sense of utterly foolish dread. How would it be, I anguished, if I couldn’t make it to the end of the session? The least of it would be humiliation, acute embarrassment, ignominious departure and annoyance to all my fellow sitters…

But there, it happened; I went, I sat. The end of the hour arrived with the mellow sound of the bell, and I had not expired! On the contrary, I was elated, filled with a sense of fulfillment and triumph at my success. I had achieved what seemed like the impossible. It had not been easy, certainly. My fractious mind had led me off along countless beckoning high- and byways. But at least I had managed to keep my rear end on the cushion and nothing dreadfully bad had happened. The world had not ended. In fact, at moments, I had actually enjoyed the experience of delightful calm. An hour, after all, was just an hour. No more, no less. It was survivable.

So it was after a few such hours that I began to envision the marriage: one hour, one painting… why not? To set aside a full hour to sit and contemplate the richness of a work of art. To really take the time to see it. The combination of my new skills as a meditator with my professional avocation as a writer about art seemed like a prospect that could prove immensely enriching to mind, body and spirit. I should give it a try.

This article is adapted from Peter’s new book, Slow Looking: The Art of Looking at Art, available here.

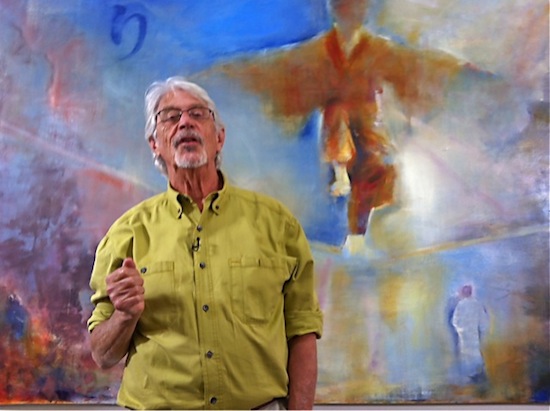

Image: The author in front of Gregg Chadwick’s painting, “Balance of Shadows.”