Art in the 1960s and 1970s was all over the place. Pop Art may have been the most famous movement of the period, and the growing stature of photography, video, and film the most long-lasting. Performance art was the most ephemeral, while an opposite approach, photorealism, described the world with deadpan accuracy.

The Museum of Contemporary Art in downtown Los Angeles has recently opened an impressive exhibition, Ordinary People: Photorealism and the Work of Art since 1968. It offers an excellent introduction to the movement in which artists painstakingly reproduced photographs as paintings, with obsessive detail and often at very large scale.

There are lots of people in Ordinary People: individuals and groups, sitting or standing, riding horses or having sex. There are also a lot of places and things: city streets lined with storefronts, highways lined with neon signs, a leather briefcase sculpted in ceramic.

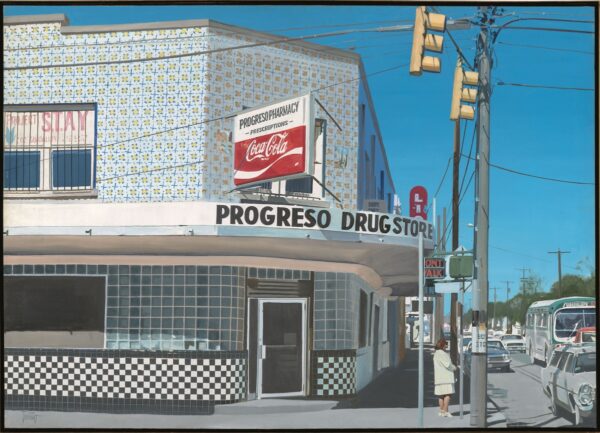

Jesse Treviño’s El Progreso of 1979 depicts an old-time drugstore on a San Antonio street corner, sporting a sign over the entrance that features a Coca-Cola ad. A woman in a white jacket waits for the light to change to cross the street. A line of cars and a bus approach the intersection. There’s nothing unusual going on here, yet it captures the reality of this specific place. It’s the sort of scene that could take place almost anywhere in America, and this universality may be a source of its strength.

Robert Bechtle, a master of deadpan images of California suburbia, is represented by Alameda Gran Torino of 1974. The Ford station wagon of the title sits in the driveway of an ordinary East Bay ranch house, alone, without people, yet the image carries a strange power. Is it the now-absurd size of the vehicle? The fake-wooden trim? Or is it simply an object of nostalgia?

Though most of the works in the show are paintings, there are a handful of sculptures including Duane Hanson’s Chinese Student of 1989. That was the year of the bloody Tiananmen Square protests in Beijing, and Hanson’s subject appears to be recovering from the battle. Wearing jeans and a T-shirt, he sits on the ground as if in a daze, still holding a protest sign while his bicycle lies nearby on the ground. It’s a powerful scene.

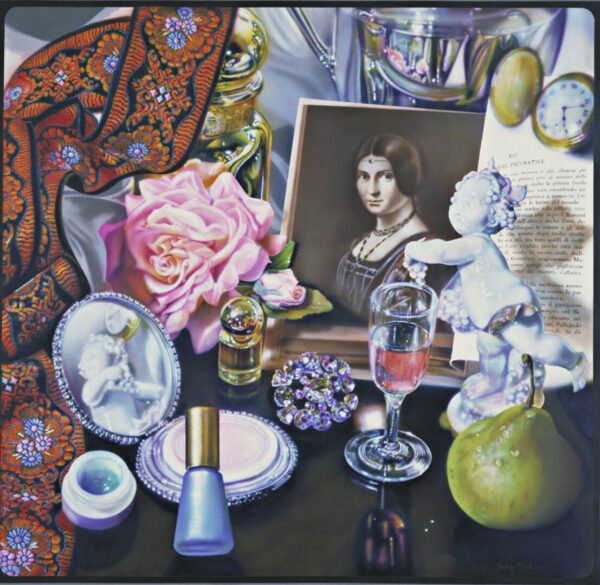

While many of the 94 artworks in the exhibition depict public spaces, there are also intimate indoor subjects including portraits and still-life paintings of ordinary objects such as rows of red lipsticks. Audrey Flack’s Leonardo’s Lady of 1974 shows a dark wooden tabletop overflowing with a woman’s things: jewelry, a pear, a rose, a glass of wine, the edge of an ornate scarf, a gold pocket watch, several small cosmetic jars, and, in the center, a square-framed reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s portrait of Frances I’s mistress, La Belle Ferronnière.

What does the painting mean? It’s hard to say. At the least it’s an intriguing bedside table of a clearly refined woman.

Ordinary People: Photorealism and the Work of Art Since 1968 runs through May 4, 2025, at the Museum of Contemporary Art, 250 South Grand Avenue, Los Angeles. The museum is closed on Mondays. An extensive catalog is published by MOCA and DelMonico Books.

Top image: Jesse Treviño (1946-2023), El Progreso (detail), 1979, acrylic on canvas; collection of Kathy Sosa, courtesy of the Jesse Treviño Art Conservancy for the Estate of Jesse Treviño; photograph by Ansen Seale.

Joseph Beuys, Artist and Provocateur

Across the street from MOCA, the Broad Museum has mounted an ambitious survey of an influential German artist, teacher, and environmentalist, Joseph Beuys: In Defense of Nature. Because much of his work could be described as conceptual or performance art, there’s lots of documentation of his projects and not so many conventional paintings and sculptures.

Early in the exhibition a visitor is confronted with what the museum describes as iconic works. There are three versions of Felt Suit from 1970 hanging on the wall, boxy men’s coats and pants made of a thick gray fabric. They’re anything but fashionable but probably would keep you warm in a snowstorm. In front of the suits is Sled of 1969, a simple wooden sled with a blanket and flashlight strapped on top.

The works apparently evolved from Beuys’s earlier experiences. He served in the German air force during World War II, was shot down in combat, and survived the winter weather in part by being wrapped in a felt blanket and perhaps transported by sled. He spent a year recovering in a hospital.

Beuys emerged from the war as a leftist with ambitions to become an artist. He attended art school, developed his craft in the 1950s, and became an environmentalist. By 1961 he was appointed professor of sculpture at the Dusseldorf Academy of Art, influencing future German art stars such as Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke. (He was fired a decade later for refusing to follow the school’s admissions policy.) Later he went on to cofound the Free International University as well as Germany’s populist-environmental Green Party.

In We Won’t Do It Without the Rose of 1972, Beuys appears to confront an anonymous man in a suit. On a table between them is a rose in a tall glass beaker, the sort of container you might see in a chemistry lab. The meaning of the work is far from clear, though it seems that Beuys the Populist is confronting The Man in some sort of negotiation, perhaps over terms of employment. In a clever juxtaposition, the photograph of Beuys is paired with a live rose in a glass beaker.

Many of the more than 400 objects in the show, nearly all from the Broad’s permanent collection, are photographs of Beuys’s artworks and projects. And in most cases, Beuys himself is front and center in the pictures, whether he’s planting trees or leading a political demonstration or hanging out with Andy Warhol.

By 1982, Beuys began to put his environmentalism into action with a work called 7000 Eichen (7000 Oaks). This mammoth reforestation project (and performance artwork) “involved planting 7,000 trees accompanied by stone markers throughout Kassel, Germany, as a means to collectively reckon with the traumas of World War II,” according to the Broad. (The museum is also co-sponsoring a program to plant 100 oak trees in Elysian Park in Los Angeles.)

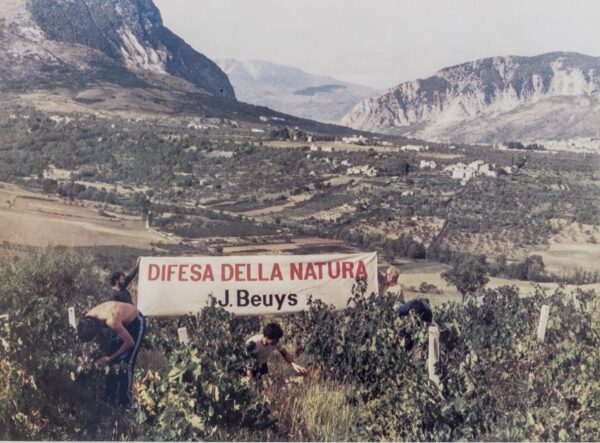

In 1984, Beuys launched a reforesting project to plant 400 trees in the mountains of northern Italy, called Difesa della Natura (In Defense of Nature). A poster for the project shows three workers planting trees while two others just behind them hold up a large banner proclaiming “DIFESA DELLA NATURA / J. Beuys.” It seems he never missed an opportunity for self-promotion.

Joseph Beuys: In Defense of Nature runs through March 23, 2025, at the Broad museum, 221 South Grand Avenue, Los Angeles. The museum is closed on Mondays. An extensive catalog is published by the museum and DelMonico Books. The exhibition is part of Getty’s PST Art initiative among Southern California institutions.