Two major exhibitions of feminist art have just opened in the San Francisco Bay Area: a sweeping look at the 50-year career of painter, sculptor, and activist Judy Chicago at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, and a lively survey of 21st-century work by women artists at the Berkeley Art Museum.

Judy Chicago: A Retrospective presents the full range of the artist’s evolving styles. There are her highly polished, colorful abstractions influenced by the California Light and Space movement of the 1960s. There are overtly feminist works from the ’70s and ’80s such as The Birth Project (top image), which vividly conveys the pain of labor but also comes across like a psychedelic view of an anatomy text. There are didactic series such as Power Play of 1985-86 and The Fall of 1993, which seem like excerpts from a grim comic book. Her latest series, The End, somberly considers her own death and that of endangered species.

Born Judith Cohen in 1939 in Chicago, she was the daughter of an art-loving mother and a leftist labor-organizing father who died when his daughter was 13. She studied art at UCLA, married young, and lost her husband in a car accident after two years of marriage. By 1970 she had remarried and changed her name to Judy Chicago, proclaiming in an ad in Artforum magazine that she did so to rid herself of “all names imposed upon her through male social dominance.”

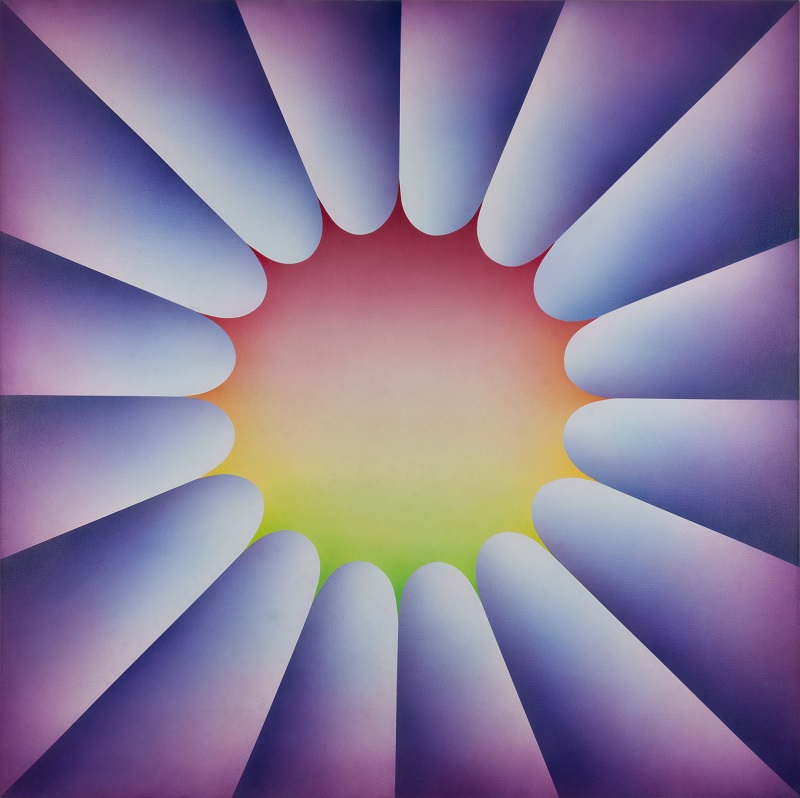

By this time she was also creating an impressive body of colorful, near-abstract works such as Through the Flower 2 of 1973. The 5-by-5-foot canvas features 16 stylized purple-blue flower petals converging on a round central area that shades from red to yellow to green like a rising sun. Chicago had learned spray painting in a 1960s auto-body class, and she employed the technique masterfully in her abstractions, creating a sense of depth with subtle gradations of color. (She also used spray painting on car hoods in the ’60s and on many of her later figurative works.)

Chicago also began to teach a feminist art program at Fresno State College in 1970, moving it the next year to California Institute of the Arts. There she found colleagues who helped form the influential Women’s Building in Los Angeles and began developing her most famous work, The Dinner Party of 1974-79.

Created with many collaborators, The Dinner Party traveled for years to 16 venues in six countries. It features a huge triangular table set for 39 famous women from history, ranging from the biblical Judith to Queen Elizabeth I to Susan B. Anthony, with customized sculptural plates for each woman. (The retrospective includes several ceramic test plates for The Dinner Party.)

Chicago’s output in the 1980s and 1990s became more explicitly gender-focused and political, not just in The Birth Project but also in series such as Power Play, which depicts the anger and cruelty of men who seek to dominate women and the world. (In one painting, Driving the World to Destruction of 1985, a crazed, muscular man is literally at the steering wheel, aiming toward a flaming apocalypse.)

In The Fall of 1993, part of her Holocaust Project, Chicago designed an 18-foot-wide tapestry mural that depicts the history of Western civilization as leading inevitably to the Holocaust. On the left, men with knives fight with women while fields are plowed. In the center is a circular space that includes part of Leonardo da Vinci’s Vetruvian Man holding a sword dripping with blood. On the right are images of industrialization and bodies being fed into Nazi ovens. Unfortunately, the horrific thesis of the work is undercut by its cartoonish painting style.

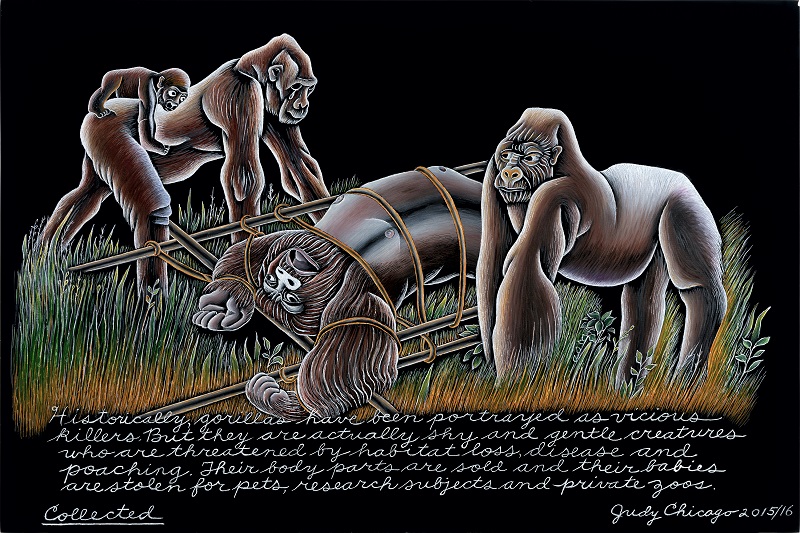

Chicago’s most recent project, presented first in the retrospective, is The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction. The series of paintings on black glass, with handwritten explanatory texts at the bottom of each image, include visions of the artist’s imagined death as well as portraits of animals facing extinction.

In Collected of 2015-16, one anguished gorilla has been captured and tied to a wooden frame for transport, while two other adult gorillas and a baby look on in dismay. The text notes that “their body parts are sold and their babies are stolen for pets, research subjects and private zoos.” It’s a disturbing image, and one of the artist’s most effective.

Judy Chicago: A Retrospective runs through January 9, 2022, at the de Young Museum, Golden Gate Park, San Francisco. An extensive catalog is published by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and Thames & Hudson.

Top image: Judy Chicago, Birth Trinity: Needlepoint 1, 1983, needlepoint by Susan Bloomenstein, Elizabeth Colten, Karen Fogel, Helene Hirmes, Bernice Levitt, Linda Rothenberg, and Miriam Vogelman. The Gusford Collection, Los Angeles, © Judy Chicago / Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York, photograph © Donald Woodman/ARS, New York.

All Kinds of Feminisms

After visiting an exhibition tightly focused on one artist, New Time: Art and Feminisms in the 21st Century at the Berkeley Art Museum offers just the opposite: a panoramic view of contemporary art made by women, featuring 140 works by 77 artists.

The plural Feminisms in the show’s title hints at its central premise, that women artists are taking all sorts of different approaches to making their art. Some are overtly political, some are not. Some are using traditional media, such as oil on canvas or photography, while others are stretching the boundaries with unconventional materials and styles.

Linda Stark’s painting Stigmata of 2011 opens the show with a striking image: a closeup of a left hand, painted in astonishing detail, down to every wrinkle and tiny ridge of the skin. The hand wears a light blue ring on the middle finger, and the word “feminist” is written — or possibly branded? — in bright red on the center of the palm. The meaning of the word is clear, but its significance is ambiguous. Is the palm raised in a greeting? Does the word announce a political stance? Does it represent membership in some group? One of the strengths of the work is how it can be interpreted in many ways.

The exhibition is divided into eight sections or themes, such as Returning the Gaze, The Body in Pieces, and Too Nice for Too Long. Yet even within one section, the works often take completely different approaches.

In the Time as Fabric section, for example, there’s Catherine Wagner’s large, elegant color photograph of the Hall of Philosophers at Rome’s Capitoline Museum, displaying dozens of busts of men only, no women. In the same section, there’s also Goshka Macuga’s photo-based tapestry Death of Marxism, Women of All Lands Unite, in which a group of women, some nearly nude, gather around Marx’s grave. The first work is a subtle indictment of history as written by men. The other is a tongue-in-cheek fantasy by an artist who grew up in Communist Poland.

Another work that draws its strength from ambiguity is Farah Al Qasimi’s It’s Not Easy Being Seen 3 of 2016. The large photograph shows a brightly colored cloak or outer garment with a floral pattern, on which is spray painted the graffiti-like slogan of the title. The cloak is held up by a pair of hands in green gloves, matching the background, while the woman doing the holding is herself not seen.

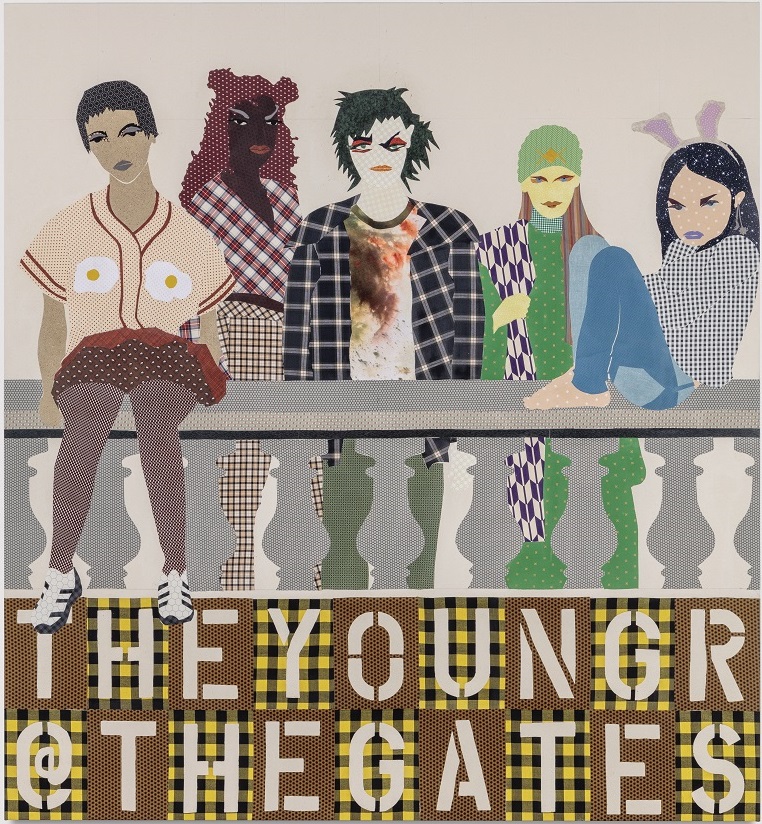

The women in Lara Schnitger’s tapestry The Young Are at the Gates of 2017 take the opposite approach. Rather than remaining hidden, these five women choose to be in your face. They stand behind or sit on a classical balustrade, wearing hipster clothes in a riot of contrasting fabric patterns. Their expressions are stern if not angry. They are clearly not to be messed with. From a feminist perspective, it’s about time.

New Time: Art and Feminisms in the 21st Century runs through January 30, 2022, at the Berkeley Art Museum, 2120 Oxford Street, Berkeley. An extensive catalog is published by the museum.