I’ll start with this: I’m sorry.

I really didn’t want to have a take, of any kind, on the discourse that has not only gripped the American literary scene by storm, but also I’ve heard even those who are not writers have caught wind of the saga between Dawn Dorland and Sonya Larson.

One thing is certain: This story is like an octopus, and has several tentacles. To try to reduce this to even two sides is inappropriate. It is a complicated, complex, sordid story. And, like most sagas in the literary world, what I always find most revealing is in the responses of others more than in the actions of the players at hand.

If you’d like to be caught up on the story, start here:

- “Who Is the Bad Art Friend” in the NYT Magazine

- “The Kindest” (the short story at the center of the #Kidneygate conflict)

- “We’re All the ‘Bad Art Friend'” by Steve Almond

- A review of “The Kindest” in New Yorker

I couldn’t possibly adequately articulate all the levels of this story, even if I tried. Even yesterday, my friend and editor, Chiwan Choi, revealed aspects of the timeline that are misrepresented in the Times piece, and of the story, that make the story even more complicated than it was already.

But, I’ll note what many believe the story to be, and what remains pertinent to what I want to address today:

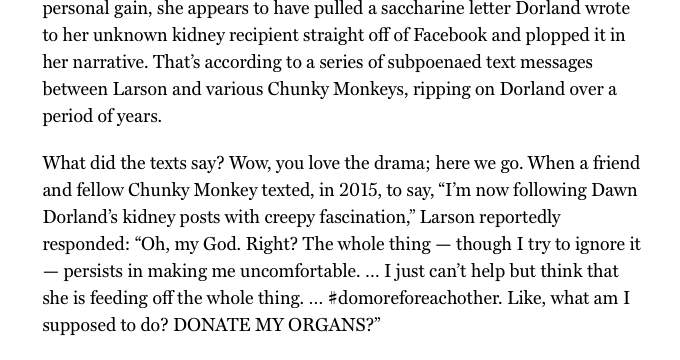

Dorland started a small, “private” (because, who are we kidding?) group on Facebook about her journey with donating a kidney. She had invited Sonya Larson, who claims [she] was not a friend of Dorland’s, but receipts would say otherwise—at the least Larson had, in years past, intimated in various ways that they were friendly. Dorland wrote Larson because she had “noticed” that Larson had been a possible lurker in a group (that Dorland invited her to)—i.e. that Larson was in the group but was not “commenting” on any of her posts.

Based on group texts between Larson and others that were revealed after Larson filed a lawsuit against Dorland (and no, not the other way around as it is stated in the Times piece), this is the moment that Larson began to work on a short story about Dorland’s “white saviordom,” and obsession with being noticed for her, indeed, very good deed of donating a kidney. Initially, Larson’s story included verbatim excerpts of Dorland’s letter to the kidney recipient. Dorland eventually learned of Larson’s story and went about attempting to discredit Larson at all institutions that Larson was affiliated with.

And there are a lot of layers and troubling facts and messages revealed in between all of those details.

The group texts reveal that Larson wrote the story, at least in part, out of spite and annoyance at Dorland’s attention-seeking behavior. Dorland is white, and Larson is mixed race Asian. These aspects of the story have been rightfully and wrongfully addressed as well as central to understanding what side you’re on. The story itself (and her group texts) reeks of ableism, and what seems a complete lack of understanding (or even research) of what it means to be a disabled person in American healthcare. Celeste Ng plays a particularly troubling role in all of this as well. Larson admits to not only plagiarizing Dorland’s letter, but with glee. Many white women have come out and said it reminded them of being the victim of Mean Girls. Many fiction writers have expressed that anything is fair game—that’s the whole point of fiction. Other hybrid and nonfiction writers have pushed back on this, saying that fiction, too, should be written with integrity and care. People of color are annoyed that this story would expose how people of color vent about white women with attention seeking behavior, because now they will all be reduced to this, and it’s much more complex than that.

But, I want to talk about one central aspect to this story that I resonate with. I am a mixed race Asian person who has not had a white savior complex (an impossiblity given that I’m not white), but I have had a savior complex. I am nothing if not a Virgo sun with immense Virgo placements (four in total, if you can believe it) and I spent my early life trying to save people. I have never gone through the process of donating a kidney or anything that would require that kind of sacrifice, but I gave all my time, energy, and attention to caring for and protecting those that I love. It took me years to see the ego in my efforts, the presumption in believing that I knew what was best for others, or even the self-gratifying quality that comes with seeing oneself as a “savior,” or a “fixer.”

I am also a twin with an intriguing narrative of how I came to be—not just in the aspect of my twinning, but also in other narrative details that have intrigued others. In fact, when I was first starting to write poetry as an undergrad and a grad student, I began to distance myself from the fiction writers in the community where I lived and still live. Often I would be sitting across from one of the fiction writers at a bar, and very subtlely, and without realizing it, I would feel that they had coerced personal, intimate material from me. Their eyes would sparkle and glint, as they asked me question after question and I, an emotionally open poet, would find myself revealing all of myself. This was before therapy, before I even knew or understood the word boundaries. It wouldn’t surprise me in the slightest if I would read a story from any of those writers back then, and discover that very intimate, specific details of my life had been lifted without so much as a conversation about it.

In fact, the voyeurism with which some fiction writers talked with me—or at times, “picked my brain” about being a twin for their twin characters—was so uncomfortable for me that I ultimately began to mistrust fiction writers. Of course, now that I have published one novel (and another on its way) before a manuscript of poetry, it is almost amusing to think of it. I suppose that because I really come at fiction by way of poetry and nonfiction, and that I come at all things from 15 years of therapy, I think that all genres of writing must come with ethical standards and wrestling with questions about how we bring the lives of others into our work, particularly the lives of others’ material that is not directly interacting with our lives.

In other words, it would have been one thing if Larson had included a letter addressed to her. It would have been yet another if she had written this story to let off some steam about Dorland’s clearly attention-seeking behavior (which is not to discredit what an immense act it is to donate a kidney for another person who needs it) and then hid it in a drawer, never to be seen from again.

But it is quite something else to immediately get the story published among institutions with huge readership and never contend with the very obvious issues of plagiarism and mining other’s lives for material based in troubling circumstances.

I am also someone who has struggled for years with writing about a story that eclipsed my adolescence and teen life—a story I won’t get into here. I’ve written about it terribly, and by terribly, I mean that I was young and naive and did not consider the ethical implications around how I wrote about it. And that was a story that absolutely happened IN my life, both to and around me, and to and around another. Some aspects of that story I fictionalized in my debut novel, but I made very specific choices, choices about allowing the players in the story a kind of privacy that I feel anyone deserves. It’s my personal belief that one can take a frustrating moment—seeing a white person center themselves in their altruistic act and fixate on that attention, for example—and complicate it in the work. But it must go beyond that initial provocation, and complicate the layers that moment reveals to us about ourselves and each other.

It’s my point of view that if Larson was the kind of person to take care in considering this story and all of its complexities, it could have been a very profound piece of fiction. In my mind, it doesn’t go beyond the caricature of the spiteful lens through which she saw Dorland. Perhaps because her need to get it published so quickly, and her motivations behind that haste, colored her viewpoint.

Fiction isn’t a get out of jail free card.

And, if it was, I wouldn’t be interested in writing it.