TIFF, the Toronto International Film Festival, is my favorite film festival of them all. It is well-curated, precisely run, and always has an exceptional mix of big Hollywood movies that will soon open in theatres, and international films you will never see anywhere else.

In this century, the vapor of terrorism has hovered over TIFF, ever since the September 11, 2001 attack took place during the festival that year. Many in the international film community recall that morning as fire trucks raced down Bloor Street, and dreadful news began to appear on CBC. The festival shut down temporarily. No one could leave; the airports were closed and communication back home was spotty.

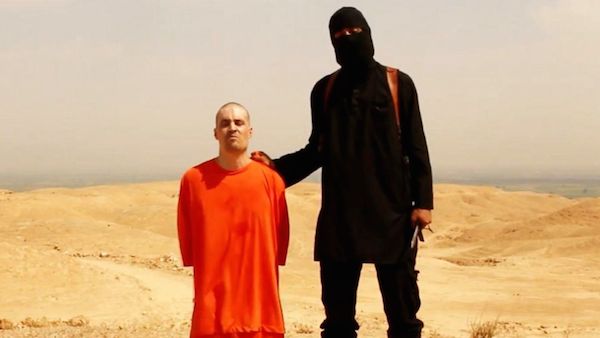

As TIFF begins this week, I’ve been thinking about that time again because we’re all still reeling from the horrifying, unwatchable James Foley and Steven J. Sotloff videos distributed by the Islamic State in Iraq al-Sham (ISIS).

ISIS is terrorist group, comprised of the most execrable specimens of humanity, yet their videos are sophisticated and speak in the international language of film. They are staged, designed and edited for maximum effect. The hooded narrator, speaking in a clipped, British accent, reminds us of the voice of the BBC. The over-saturated red tones have clearly been color-corrected. I called the videos “unwatchable,” and they are, which was precisely the point ISIS was trying to make: That they will craft narratives we cannot bear.

Where did ISIS, and many others, learn their video lexicon? From watching media content. Film language has become universal; the blowback is that it is accessible to all. Film has truly become the international vernacular, far more broadly spoken than English or Chinese. Everyone’s mobile device contains a movie camera, editing suite and distribution platform. With the means of creating and distributing movies now broader and more democratized, its jargon has become the common tongue. We all see the world and express ourselves through cinema and its media counterparts.

ISIS is not the first terrorist group to use media to convey its message. Osama bin Laden provided videos and audio recordings, which were played on Al Jazeera. According to a recent study, 90 percent of organized terrorism on the Internet uses social media; ISIS first posted its video on Twitter. Terrorist groups always find ways to disseminate their ideologies.

So what’s changed? Beginning with the introduction of consumer digital cameras in the late 1990s, through the launch of YouTube in 2005 and Twitter in 2006, to the establishment of multiple DIY video platforms beginning in 2012, media technology and media theory have converged. The White House and North Korea both have official YouTube channels, and Israel and Hamas release divergent videos of their current conflict. Because everything that happens can be documented, we now exist in a society where if there is no video, it didn’t happen.

Which is why we shouldn’t be surprised when ISIS communicates with the rest of the world in our language. What can we do? One response to the expropriation by evildoers of our art form is to drown their work in an ocean of fine cinema.

TIFF is an example. It is a democratic and inclusive enterprise. There will be delegates from more than 70 nations in Toronto this week, and audiences will be able to view films from more than 50 countries. Watching these movies in an international community of fellow artists (along with avid Canadian citizens) offers a comprehensive experience of beauty and thrill. It is a series of windows on the world.

Fundamentalist, terrorist groups like ISIS don’t like film except for their own ends. They execute people who watch foreign media. In a number of countries cinemas are banned. And yet, we know that the more people are exposed to points of view other than their own, the more moderate they become in their political and social beliefs.

It’s one reason fundamentalist groups discourage the arts and education. Before the word “liberal” became pejorative in the United States, this was called a “liberal education,” and its ideal was to prepare people to live in a free and humanitarian society. In the same way, we all find more common ground when we watch each others’ movies. On the geopolitical level, I doubt that our policy makers watch the films from the more than 150 countries in which the US has military deployments. What might they, and we, learn? A deeper understanding of the humanity of the people we call “foreigners,” and, I trust, a far greater reticence to engage in military enterprise.

The cinema output of filmmakers around the world is now readily available, it’s just that few of us are watching. It’s hard to have a film from Senegal, or Iran, or Ukraine command your attention on your laptop in the midst of daily life. That’s why everyone who cares and affects global actions needs to have a space and time to see a wide range of movies in the community of others. We should all come to TIFF, or experience something like TIFF: citizens of every nation of the world, civilians and militias, the dominant and the oppressed, those who forge terror and those under its thumb.

Movies are a dialogue, and may be instruments of joy or pain. Although the language of film has become part of the terrorist playbook, cinema is the corrective as well.

At TIFF, Adam Leipzig will be moderating a panel on Disruptive Ways to Invest Profitably in Independent Film on September 6 at 2pm. The panel is co-presented by Raindance.

Top image: A scene from ’71, directed by Yann Demange, screening at TIFF this year.