It’s no secret that Los Angeles is home to thousands of Koreans. L.A.’s Koreatown district is filled with Korean eateries, high-rise offices, condominiums and retail stores. Take a drive along Wilshire, Western or Vermont and see Korean neon signs shine beautifully in the California night. The poet and community organizer Tanya Ko Hong celebrates this spirit and the Korean diaspora in Los Angeles through her poetry, translation and by connecting the dots between the city’s multicultural citizens. This idea is something she decided to do while finishing her MFA at Antioch University several years ago. Since this time, Hong has hosted literary events that bring together three generations of voices and writers from other cultures.

I have been to several events hosted by Hong and each reading featured poetry being read aloud in both Korean and English. One of her recent events also included a few poems read in Spanish by former Los Angeles Poet Laureate Luis Rodriguez. Hong knows that these languages are backbones of Los Angeles and that the only way to truly represent the city is to have poetry spoken in each of these tongues.

“I enjoy bringing immigrant and multilingual voices together,” she says, “and serving as a literary, cultural and generational bridge to remind everyone of what it is like to be human being.” Hong bridges literary communities both culturally and generationally. Furthermore, she adds, “As an immigrant myself, I know what it feels like to be invisible, voiceless, and powerless.”

Looking Back to Look Forward

Hong’s many poems address the intersection of Korean and American culture. In her poem, “Look Back,” published in Cultural Weekly in 2015, she writes about three instances of Korean-American encounters: her teenage daughter in high school, her parent’s paper divorce and an interview with an immigration officer. In one of the most powerful stanzas she writes:

Yes, we want to run away from the truth.

We want to not remember.

We want to protect— not to cause problems.

We learn to pretend—

Delete names.

Disconnect.

Hong uses her work to reconnect the forgotten stories. She is not afraid to bring up the elephant in the room. Her work is guided by several purposes. In addition to bridging communities with the events she has hosted, she has used oral history in her poetic practice and also uses oral history to get stories out that have remained mostly unknown, especially the topic of Comfort Women.

In late 2017, the website Women’s Voices Now published Hong’s poem on Comfort Women.

Before the poem is a short preface that explicates how Comfort Women is “’a euphemism for the estimated 200,000 South Korean girls and young women who were subjected to sexual slavery in Japanese brothels before and during the Second World War.’ Only in 2015 did the Japanese government issue a formal apology to the survivors. Public acts of commemoration in South Korea, however, draw criticism from the Japanese government.”This statistic was quoted from an article on the site, Women in the World.

Before the poem is a short preface that explicates how Comfort Women is “’a euphemism for the estimated 200,000 South Korean girls and young women who were subjected to sexual slavery in Japanese brothels before and during the Second World War.’ Only in 2015 did the Japanese government issue a formal apology to the survivors. Public acts of commemoration in South Korea, however, draw criticism from the Japanese government.”This statistic was quoted from an article on the site, Women in the World.

In Hong’s segmented poem, she reveals several different short narratives about Comfort Women and their plight. She fills in the details and reminds the reader that: “They called me, wianbu— / a comfort woman— / I had a name.” Hong has published four books, one of them in Korean is called Comfort Woman.

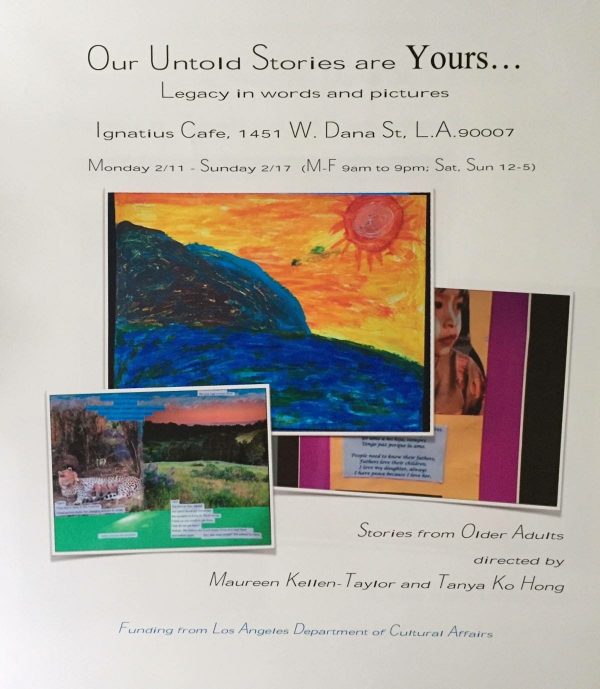

Dr. Maureen Kellen-Taylor is a Visiting Scholar at the USC School of Gerontology and an Artist in Residence with the Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs (DCA). Dr. Kellen-Taylor has partnered with Hong on multiple events and workshops. She recently told me: “I invited Tanya to collaborate with me in my DCA funded residency called ‘Our Untold Stories are Yours.’ This theme fit well with her powerful work in publicizing the plight of Comfort Women. Thus Tanya brought deep understanding of the project’s intent as well as her characteristic enthusiasm and energetic commitment. Although she had never worked with groups of older adults before, she effortlessly moved into encouraging them to tell stories. These she translated from Korean to English to make the stories more accessible.”

In April 2017, I went to an event Hong hosted in Koreatown at the House of Writers Gallery on James M. Wood Street just west of Hoover. Co-hosted by Poets & Writers Magazine, the topic of the roundtable discussion was about bridging literary communities across California. Hong asked the poet and educator F. Douglas Brown to read the English translation of a celebrated Korean poet. Hong had studied with Brown in the MFA Program at Antioch and they both share the value of using poetry to educate and uplift.

Following Brown’s recitation, Hong spoke about an upcoming event she was hosting the following Sunday which commemorated the 25thAnniversary of the Los Angeles Riots aka the Rodney King Rebellion. Featuring poets from Leimert Park and Highland Park, the event was intended to bring the Korean, Latin American and African-American communities together.

A few months later, Hong invited me to the Korean Cultural Center in the Miracle Mile on Wilshire Boulevard. The focus of the night was on the Korean National Poets: Yi Yook-sa, Yun Dong-ju, Han Yong-un , Lee Sang-hwa. These were Korean poets that were persecuted by the Japanese during the early 1940s when Korea was occupied by Japan. One of them, Yun Dong-ju died in a Japanese prison at the age of 27. They were all resistance poets and their work is now considered heroic and been the subject of many recent studies because of the extraordinary conditions they faced.

Translation and Creation

An excerpt from a documentary film was shown, several of their poems were read in both English and Korean and a short talk by a Korean Literary Scholar spotlighted the significance of these four writers. As much as Los Angeles has a storied legacy with its Korean residents, this was the first time these Korean poets were celebrated in a local event. Hong is proud to have the translations of these poems read. “Translation is an act of creation,” she says. “We must value translation because without it, we aren’t able to learn about lives largely different from our own.”

About a year later, Hong hosted another event in Koreatown. This one in August 2018 was held at the Korean Daily Newspaper next to Southwestern Law School, just east of the old Bullocks Wilshire Department Store and in between 7th and Wilshire. As noted above, one of the poets present that night was former Los Angeles Poet Laureate Luis Rodriguez who read poems in both English and Spanish. Other poets present were the Leimert Park poet and USC Professor Hiram Sims and the UCLA Extension Professor and Founder of the Los Angeles Poetry Festival Suzanne Lummis.

Lummis has been teaching poetry for over 25 years. Her relationship with Tanya Ko Hong has been symbiotic for the pair. Lummis recently used one of Tanya’s poems in her video series about the Poem Noir. “I met Tanya Ko decades ago and she told me that she longed to study with me but couldn’t till her children came of age.” Lummis shares, “Years later she showed up in my UCLA Extension Writers Program class — in fact, three or four back to back classes — and applied herself with determination and passion. Now she’s among the world changers. Though I’m an aficionado of Noir, I must admit — some stories do have a happy ending.” Lummis used one of Hong’s poems in her “Poem Noir” video series.

Hong’s event in late September 2018 was at the Korean Consulate on Wilshire Boulevard in the Miracle Mile district. The event honored the work of the Korean poet, Yi Sang. Sang lived from 1910 to 1937 and died in a Japanese hospital after he was arrested and imprisoned during a trip to Tokyo. Later celebrated as Korea’s most notable modernist, his work resisted Japanese occupation but he was not so much of an activist as he was a Bohemian that was oblivious to everything around him except his literary pursuits. Incorporating surrealism and nonreferential narrative techniques in his poetry, Sang is an enigmatic figure in Korean literary history and a poet whose work has been rediscovered by literary scholars in recent years.

On this particular night several of Sang’s poems were read in both Korean and English. I was one of the English readers. I read two of the pieces that were both prose poems somewhat akin to the surreal prose poetry of Baudelaire in Paris Spleen. The opening segment of Sang’s Poem No. XV states: “I’m in a mirrorless room. Naturally the I in the mirror has gone out. I’m trembling now in fear of the I in the mirror. Has the I in the mirror gone somewhere to plot what next to do to me?”

This dreamlike inquiry and reflection epitomizes the spirit of Sang’s probing work. His seven poems I heard that night and later read all share a sense of anxiety and uncertainty connected to his imprisonment and the volatile political conditions between Japan and Korea in the 1930s and 40s. This experience piqued my curiosity into Sang and his contemporaries’ writing.

Hong revels in introducing the work of Sang and other Korean poets into the 21stCentury poetic conversation, especially in Los Angeles with the deep Korean presence in the city. The alienation that Sang writes about is not only parallel to Baudelaire’s 19thCentury musings on Paris but also similar to the immigrant experience in Los Angeles of 2019. Hong loves how poetry can characterize so many different emotions and forge a bridge between international citizens and cities like Seoul, Tokyo, Paris and Los Angeles.

Hong revels in introducing the work of Sang and other Korean poets into the 21stCentury poetic conversation, especially in Los Angeles with the deep Korean presence in the city. The alienation that Sang writes about is not only parallel to Baudelaire’s 19thCentury musings on Paris but also similar to the immigrant experience in Los Angeles of 2019. Hong loves how poetry can characterize so many different emotions and forge a bridge between international citizens and cities like Seoul, Tokyo, Paris and Los Angeles.

Following the reading I met some Korean poetry scholars and we connected on the duende of Sang’s poetics. After listening to these poems, I thought about how themes like erasure and alienation are more relevant than ever. These tropes extend across centuries whether it’s Korean poets in the 1930s, the Vietnam era or Trump’s America. Tanya Ko Hong is connecting the dots between these early 20thCentury Korean poets and 2019.

Hong is right on time with her vision because many teenagers that are not even Korean have started to like K Pop Music and the Korean actress Sandra Oh recently hosted the Emmy Awards. She ended up winning an Emmy that night in front of her parents. Undoubtedly, the Korean presence in popular culture has become much more prominent in America in the last decade.

Now in 2019, there are many Korean-American writers making noise across the literary landscape. In 2017, the Korean-American author Min Jin Lee made waves with her award-winning novel, Pachinko. Tanya Ko Hong and Min Jin Lee are joined by many other stalwart Korean American scribes like Steph Cha, Alexander Chee, Chiwan Choi, Don Mee Choi, Franny Choi, Nicole Chung, Cathy Park Hong, Alice Sola Kim, R.O. Kwon, Janice Lee, Julayne Lee, Linda Park, Margaret Rhee, Nicky Schildkraut, Monica Youn and many others.

Tanya Ko Hong is doing her part with writing, collecting oral history, translating and organizing event after event. The several events of hers I have been to over the last three years were all educational and uplifting. Hong is shining a light on Korean poets that were previously unknown in Los Angeles and continuing workshops with Korean Seniors and multicultural poets across the city. She sees translation as creation and loves to help people tell their untold stories.