Just before the outbreak of violence in Gezi Park, in Istanbul, I spoke with Turkish director Belmin Söylemez about her film, Present Tense, which recently won the New Directors Prize at the San Francisco International Film Festival. The prize is granted to a first-time filmmaker whose work exhibits a unique artistic sensibility. In the words of the presenting jury, Present Tense was chosen for “its intelligence, sensitivity, humor, honesty, humanism, great performances and its refusal to supply easy answers or neat solutions to the tough questions that confront a structure of feeling shaped by the powerful and also alienating forces of global capitalism, urban redevelopment and consumerist marketing.”

Lonely and down on her luck, the unemployed Mina at the heart of the story, accepts a job as a fortune teller in a café in Istanbul, reading coffee cup futures for paying customers. Mina ignores multiple eviction notices and bides her time squatting in her apartment that is scheduled to begin construction any day, while plotting her escape to a more promising future in the United States. There is a pervasive feeling of powerlessness in the lives of the three central characters in Present Tense, all of whom are struggling to shape their destinies in the rapidly changing city, where little apparent heed is paid to their existence. Söylemez has managed to capture the unrest that has been fomenting in her homeland, at the critical moment just before its eruption. How prescient.

This interview with Söylemez was conducted on Thursday, May 30, by Skype. Two days later, on Saturday, June 1, Söylemez forwarded me a petition authored by a friend who was living in Taksim Square, to save Gezi Park — one of the last-remaining, public, green-spaces in the city — from destruction. By government decree from Prime Minister Erdogan, Gezi Park is set to be remade into a shopping mall within Ottoman-era replica army barracks. Erdogan has been criticized for overstepping his powers, imposing his “Napoleonic” will through sweeping urban redevelopment in Istanbul. In 2012, he readily won re-election with over fifty percent of the vote, but he has been perceived of late, as a leader dismissive of the opinions of those who did not vote him in, and he has been criticized for the use of excessive use of force by riot police in responding to protesters with tear gas grenades and water cannons, which has left 4,300 injured and 3 dead in the two weeks of conflict to date.

When I inquired at that time if Söylemez was safe, she responded:

“We are safe at the moment. Although almost everyone here has had their taste of teargas. Taksim Square and Gezi park now are full of people day and night, coming from all neighborhoods, different towns. The park has become a symbol of freedom of speech and the right to protest, a symbol of the right to free assembly.”

Present Tense has yet to be picked up for distribution outside of Turkey; however, as curiosity about the conditions leading up to this conflict reach an all-time pitch, foreign distributors may come knocking for an opportunity to share Present Tense with the global community. As goes the ancient Chinese proverb: “May you live in significant times,” a blessing and curse for artists and filmmakers who dare to be relevant.

Here is the interview from May 30, 2013, just prior to the start of the conflict.

Sophia Stein: When you arrived in San Francisco, your very first night, you were awarded the New Director’s Prize ($15,000) at the San Francisco International Film Festival. In your acceptance speech, you commented that in your first impressions, San Francisco struck you as very similar to Istanbul. In what ways?

Belmin Söylemez: Well, the bridges — we have two bridges connecting the continents, with the sea in between. And the hills — Istanbul is a city built on hills. I like hills because they give the city perspective. Istanbul is also a very cosmopolitan city, and I could tell that San Francisco is cosmopolitan and multicultural, as well.

S2: How have things changed during the course of your lifetime in Istanbul?

BS: The city is changing very quickly. They are calling it urban development, but its gentrification. You can witness it happening in the film. Historical cinemas and buildings are being demolished. A part in the city-center is being destroyed. Many characteristic buildings and neighborhoods are being remade. It is a huge change, and it is making me and a lot of other people very uncomfortable, because the inhabitants are being pushed out. I really wanted to reflect that ongoing change in my film.

S2: Who do you feel is responsible for pushing out the inhabitants?

BS: We can call it the system, but I think it’s a universal thing. It’s global capitalism. Historical, characteristic places are being turned into shopping malls. Of course. I’m not against change, but the inhabitants and the [essential] characteristics should be preserved, without which tourism couldn’t even exist.

S2: Were you born and raised in Istanbul? Have you lived there your whole life?

BS: I was born in Istanbul and raised there for a little bit. Then, because my father was a diplomat, we traveled a lot. I lived in Ankara, the capital city of Turkey; we were in New York and London for a while. My [extended] family, my grandparents and the rest, basically lived in Istanbul. So we came to there for holidays every year, and we spent every summer there. When I was coming and going, I could witness the changes that were taking place in Istanbul more clearly, the stark differences. My parents and my brother settled in Ankara, but I chose to live in Istanbul.

S2: How would you characterize the difference between the Ankara and Istanbul?

BS: Ankara was formed during the Turkish Republic, so it’s a kind of new city. And Ankara has no sea. I like Istanbul because it’s very beautiful – the sea, the two continents … It’s Europe and Asia, east and west at the same time — it’s a cliché, but it’s true. You can live in Asia and work in Europe or vice-versa; you can just catch a boat and cross to the other side. Istanbul has all these magical aspects. It has a kind of dreamlike quality, for me.

S2: It is ironic that apparently more people will see your film Present Tense abroad, than in Turkey?

BS: Yes, unfortunately there is a big problem with distribution of independent films in Turkey. The characteristic film theatres are closing down one by one, and it is very difficult for art-house films like ours to get distribution in the country now. We are hoping to get it into the cinemas here in September.

S2: How do you feel about digital distribution?

BS: I see it as a positive thing. It’s liberating. You can get to see a lot of world cinema, which you won’t be able to see in theaters. But at the same time, you know — the magic of watching a film in a theater, when it’s all dark, and you’re by yourself, and you going to that world, that’s something else! So, I miss that.

S2: Tell me more about the inspiration for your story.

BS: I went through a similar period to the main character, Mina, where I was unemployed and lonely and wanted to move abroad. Friends of mine (mostly young women) went through similar periods. So while going through this unclear and ambiguous time, we were telling each other these coffee cup stories and trying to give one another hope. I was always thinking that I should start writing about this, and I did. I started taking notes about seven years ago. As the story evolved, I started writing together with Haşmet Topaloğlu, who is also the producer of the film. We outlined together, wrote our scenes separately, and then would look at it together. But the most fun was when we were writing the coffee cups scenes, because we were really drinking a lot of coffee and trying to read each other’s fortunes from the coffee cups, and writing it down at the same time. That was a lot of fun!

S2: In the U.S., people read tarot cards, but not coffee cups so much. Can you tell me a bit about the tradition of reading peoples fortunes in coffee cups in Istanbul?

BS: My grandmother did it and my mother did it, so I grew up actually hearing the coffee cup stories. It’s a thing in the Balkans region and the Middle East. It used to be done more at home, as a means of gossip — communication between women behind closed doors, basically, but now it has gone out more into the street. There are lots of those cafés that you see in the film, where young people go to find some hope. A lot of university graduates who are unemployed are working in them or frequenting them as customers.

S2: Did you ever work as a coffee-cup fortune reader?

BS: That was purely from my imagination. While we were looking for funding, I had friends who would suggest, “Why don’t you start working in one of those cafés, that’s how you can get the money for your film!” It’s a very low budget film, made mostly with our own means and the support from family and friends. Near the end, we got some post-production funding from the Ministry of Culture.

S2: What does the title of your film, Present Tense, mean to you?

BS: It has a double meaning. Mina is trying to escape from the present into the future. All the characters in the film are trying to escape into a new life in the future, but they’re stuck in the present. At the same time, Mina is trying to learn English. So Present Tense also refers to her struggle to learn English. In the beginning of the film, Mina is a lonely woman looking for hope; at the end, there is Fazi, so there is friendship and solidarity.

S2: I am curious about your relationship as an artist to your homeland and to your native language. Are you committed to staying in Turkey, or do you still identify with the desires of your protagonist, to escape?

BS: There are times that I do want to escape. And I do escape for a while, but then I always feel that I’m drawn back here. I think it’s a kind of instinct that is difficult to describe. Istanbul, Turkey – it’s my city and my country, but at the same time, life here is what gives me inspiration for my work. It is such a dynamic culture and city… even though it’s changing a lot, it’s also inspiring me a lot. So I cannot think of myself living elsewhere. Obviously, to visit other cultures is very important. But we always return to our own homeland, I think, where we get our inspiration. I cannot say that I completely belong here, but I feel at home here.

S2: What are some of your upcoming projects?

BS: I have two narrative projects in mind, both inspired by life stories. One of them is set once again in Istanbul today; it is about actresses and the art circles, with a realistic feel. The other story is set in the south of Turkey, on the Mediterranean coast; it is a more surreal story of a young woman. I have strong feelings for both projects. I will have to decide soon which one I’m going to concentrate on making next.

S2: There are more films being made in Turkey at present than any place else in Europe, except for France. To what do you attribute this Turkish filmmaking renaissance?

BS: The awards that some Turkish filmmakers have won — for example, Nuri Bilge Ceylan (Once Upon A Time in Anatolia, Three Monkeys) — I think, have encouraged new filmmakers to make stories about themselves and their own worlds. There were lots of social issues that needed to be addressed and many stories that needed to be told. We have a group, which we call The New Cinema Movement, where directors and the producers come together and talk about distribution and other problems. Cinema in Turkey is booming, with many up-and-coming women directors.

S2: Did you have an opportunity to see some of the other films at the San Francisco International Film Festival while you were visiting?

BS: When we arrived, our driver, David G., picked us up from the airport wearing this wonderful 1930s gangster outfit, and whisked us off to see the silent movie, Waxworks, in the Castro Theatre, which was a wonderful experience with live music! We used to have this film theater in the center of the Istanbul, The Emek Film Theatre, which was recently destroyed, unfortunately, despite the many protests. So, it was affirming to see such a wonderful, historic theater being so well-maintained, and watching a movie there.

________________________

Out of concern about the escalating tensions in Istanbul, I emailed Söylemez just last night for an update. The following is her response from Wednesday, June 12, 2013:

Sophia Stein: If you had to predict the future, to read the coffee cup for this conflict, what do you see?

Belmin Söylemez: I see a long, difficult winding path with trees and many people. The people all seem different, but they also seem to be united with the same energy. It looks like they are speaking or reaching out, but the path seems blocked at the moment. In other words, this path also looks like a milestone, a turning point in which many different people are saying ‘no’. This is a simple human ‘no,’ not a politically ambitious one.

S2: What is the best possible outcome, in your perspective?

BS: The government realizes that they are making a mistake. They pull back the police force and listen to the voice of the protesters (their own citizens). The park area stays a park. Officials responsible for violence and misuse of their power are questioned in court. The government re-evaluates their so-called ‘urban development policy’ in favor of the environment and low-income-people. All citizens of the country have a say in issues that concern their lives: like public spaces, education, health …

S2: And the worst case scenario?

BS: I don’t even want to think about it. — The most obvious would be: The government destroys the Gezi park which symbolizes the protests and the voice of the public. They build a replica of the Ottoman Barracks. The barracks contain a shopping mall with all the same chains that you can find within 200 meters. Taksim Square becomes a rectangle of concrete buildings with no open space and no green at all.

S2: Do you continue to feel safe in your home in Istanbul? Or will you temporarily evacuate the city?

BS: I feel safe but also worried. Still, the neighborhoods away from the demonstration areas have no risk. I don’t have any plans for leaving the city for that reason.

S2: Are you participating in the protests? As either a protester? Or documentarian?

BS: Like many filmmakers and artists, I have been going to the park to support the people there. We, as filmmakers, have established a network for the Gezi Park protest. We have a tent in the park where filmmakers, actors, artists and film technicians show their support to the protesters and also talk about what could be done in that process. Moreover, I have participated in a collaboration of filmmakers, in filming a documentary about the park and the resistance there.

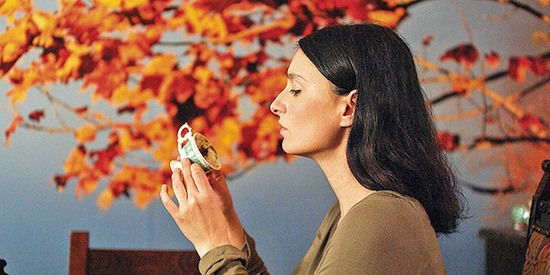

Images, from top: Director Belmin Söylemez; CNN news footage of protests; two scenes from ‘Present Tense’