At the start of Paula Vogel’s Mother Play, presented by Second Stage at the Hayes Theater, I thought, “Oh no, not another monster mother drama!” The opening of this semi-autobiographical memory work seems similar to classics such as The Glass Menagerie and Long Day’s Journey Into Night, both of which Mother Play star Jessica Lange has headlined on Broadway. The dominating matriarch here is addicted to alcohol just as Menagerie’s Amanda Winfield clings to illusions of her gracious Southern girlhood and Journey’s Mary Tyrone turns to morphine to avoid the pain of the present. While Vogel’s work may be influenced by Tennessee Williams and Eugene O’Neill’s family dramas, she has created a unique, funny, sad and touching piece, employing her own backstory as the source material. As Tolstoy famously wrote in Anna Karenina, “All happy families are alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

Credit: Joan Marcus

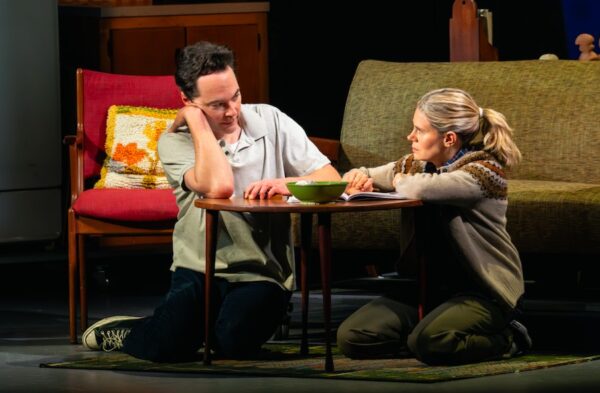

Subtitled A Play in Five Evictions, Mother Play chronicles the fractured relationship between Phyllis (a stunning Jessica Lange) and her two children Carl and Martha (equally strong Jim Parsons and Celia Keenan-Bolger) as they move from a series of apartments in and around Washington, DC from 1964 to the present. Like Amanda in Menagerie, Phyllis has been abandoned by her husband and must earn a living to raise her kids. Both offspring come out as gay as they enter adulthood, much to Phyllis’ disappointment. Carl later succumbs to AIDS and Martha grows into her lesbian identity while mourning her beloved brother. Vogel has explored her relationship with her sibling in a previous play, The Baltimore Waltz. Here she focuses on her mom and how the parent-child bond frays and nearly unravels over the decades.

Credit: Joan Marcus

Much like Tom in Menagerie, Martha acts as a narrator, setting the scene for each “eviction” as the three-member family, moves, splits apart and reunites. Unlike Tom, Martha ultimately stays with her parent. Vogel finds humor, pathos and compassion in the seemingly ordinary chronicle as the children realize their true nature, the mother rejects them at first, gradually comes to grudgingly tolerate their sexuality, but never fully accepts them. Director Tina Landau balances the laughs with pathos. A riotous sequence with animated cockroaches dancing all over David Zinn’s mobile set contrasts with a screaming confrontation between mother and children. Both are equally impactful and truly felt.

Credit: Joan Marcus

The acting is as centered and realistic as any on Broadway right now. Lange’s Phyllis is as memorable as her Mary Tyrone as well as her magnificent work in the recent TV Feud series as Joan Crawford and the ghost of Truman Capote’s mother. She displays all of Phyllis’ facets, ugly as well as attractive. She has two show-stopping moments. First in a series of hilarious phone calls to a negligent landlord, complaining about those dancing roaches in her basement apartment, she is riotously tough and determined to make her point and plea in vain for an exterminator. Then later in the play, she performs a seemingly drab solitary evening at home, but endows it with subtext. Without uttering a word, Lange fixes a pathetic microwave supper, smothers it with tabasco sauce, plays a favorite record, attempts to deal a hand of Solitaire, and finally consults a crystal ball, all conveying Phyllis’ desperation for human contact and alienation from her children. Keenan-Bolger and Parsons skillfully chart Martha and Carl’s journeys from precocious, intelligent teens to conflicted adults.

Set designer David Zinn places furniture on mobile platforms to facilitate suggestions of various apartments and convey the impermanence of the family’s homes. Toni-Leslie James’s costumes are period perfect and projection designer Shawn Duan provided those cute dancing roaches. This is a memorable Mother Play, distinct from its predecessors by Williams and O’Neill.

Credit: Matthew Murphy

Amy Herzog provides us with a very different kind of mother in Manhattan Theater Club’s revival of her 2017 play Mary Jane, now at the Samuel J. Friedman. Mary Jane, played Rachel McAdams in an impressive Broadway debut, face a radically different challenge. Like Phyllis, she has been left by her spouse, but Mary Jane does not dwell on her misfortune like her counterpart in Mother Play. Her only child Alex suffers from a laundry list of illnesses, rendering him unable to talk, breath or sit up on his own at age two. Without melodrama or histrionics, Herzog offers an almost documentary view of Mary Jane’s struggles with live-in nurses, plumbing issues, the grind of getting through the day, and her son’s complex medical needs.

The production closely resembles Anne Kauffman’s original one from the New York Theater Workshop, except Lael Jellinek’s set is now more elaborate with a stunning effect once Alex’s condition takes a turn for the worse (No spoilers). Also, Herzog has put in a minor edit, acknowledging the post-COVID pandemic era and the pressure on Mary Jane to return to her office job. Like Landau’s work in Mother Play, Kauffman’s staging is almost invisible in its simplicity and heartbreaking in its attention to the small details such as the matter-of-fact casualness that the characters exhibit when dealing with Alex’s vital signs and maintaining the various machines which keep him alive.

Credit: Matthew Murphy

The same is true for the five-woman company. McAdams carefully calibrates Mary Jane’s sunny optimism not to be too saccharine and allows the smallest break in her composure to have maximum impact late in the play. The four other actresses double up as friends, doctors, nurses and supporters, endowing each with a separate and strong personality as well as reams of subtext. Brenda Wehle is strikingly sympathetic as a friendly building superintendent and a compassionate Buddhist nun. Susan Pourfar garners guffaws and tears as two very different mothers with situations similar to Mary Jane. April Matthis is steely but soft-hearted as a no-nonsense nurse and doctor. Lily Santiago brings dimension to a young friend and a kind music therapist.

Like Mother Play, Mary Jane does not have “action” or “plot” in the conventional sense and there is no climactic resolution. Both plays are what we used to call “slice-of-life” dramas and their servings are enriching and insightful into motherhood in particular and the human condition in general.

Mother Play: April 25—June 16. Second Stage at the Hayes Theater, 240 W. 44th St., NYC. Running time: 100 mins. with no intermission. 2st.com

Mary Jane: April 23—June 16. Manhattan Theater Club at the Samuel J. Friedman Theater, 261 W. 47th St., NYC. Running time: 100 mins. with no intermission. telecharge.com