A play with as enticing a title as the one-word Witch is hard to pass up and this season opener in The Geffen Playhouse’s smaller space, with its mash-up of periods, pitfalls and prevarications, is a wild ride.

Playwright Jen Silverman took big chances when she pilfered some of the convoluted plot and characters from a 1621 Jacobean tragicomedy, The Witch of Edmonton, written by a committee of three: William Rowley, Thomas Dekker and John Ford. She simplified the overcooked 17THcentury shenanigans and shaped them into a sleek 21stcentury satirical comedy. Or perhaps tragicomedy. Costumes and action stay in period, but what comes out of the characters’ mouths is pure 2019. The dress and the restructured remains of the original plot are Jacobean, the language not. These people speak Millennial.

It’s a highly impudent idea, as well as a brave one. Silverman mostly makes it work, even as it gets slightly out of hand. Still, this tale of suspected witchcraft, inheritance mayhem, a secret marriage, an inconvenient pregnancy and a devil named Scratch makes for a lot of high jinks.

Scratch, a self-proclaimed junior salesman in deviltry (played by the dashing Evan Jonigkeit), is making the rounds in the village of Edmonton in search of souls to buy, and while most of his marks are easy prey (I’ll give you my soul if you give me that), he forms a more challenging relationship with Elizabeth Sawyer (Maura Tierney), an ostracized woman of the town falsely accused of witchcraft.

Elizabeth is fully fed up with being considered a witch by her fellow villagers. In Scratch she finds a kind of kindred spirit with whom she’s free to disagree. The two become smartly involved in a sly bit of gamesmanship as they contemplate the proliferating bad behavior among the less enlightened beings that surround them. Scratch may well have met his match when it comes to negotiations, because Sawyer is really good at dissecting what kind of deal could be considered good when it comes to selling your soul.

The Lord of the Manor in town is the widowed Sir Arthur Banks (Brian George) who has taken a fancy to Frank Thorney (bad boy Ruy Iskandar), the priggish son of a local farmer. Sir Arthur likes Frank better than he likes his own son Cuddy (Will Von Vogt). Cuddy is a limp sort of guy of indeterminate gender, whose only declared passion in life is Morris dancing. Sir Arthur toys with the idea of making Frank his heir, instead of Cuddy, and goes so far as to make Frank an offer—until he discovers that Frank is secretly already married to Winnifred, the maid at the Manor (an incisive Vella Lovell), who also happens to be pregnant with his child. Uh-oh.

What started as a comedy suddenly becomes less predictable. When the Morris-dancing Cuddy does something quite out of character, it changes the game. The plot thickens exponentially. Where there had been many takers when it came to those your-soul-for-your-favorite-thing exchanges presided over by the devilish Junior Salesman, the stakes are suddenly a lot higher.

By now, Scratch and Elizabeth have become close. They understand each other. More dangerous still, they understand the world in ways the others don’t. And her demands of him, in exchange for her soul, rise to a different plane. The mood alters and the comedy, which delivers a very 2019 reveal, is a comedy no more. It changes in pretty much every way.

Given all this, Witch becomes a more major accomplishment than it initially promised to be. That change in tone and depth is a risky move that must have taken some gumption, and while the clash of styles keeps us amused or on edge throughout, it gradually throws us suddenly and completely off balance. The very 2019 endgame is a downbeat surprise well worth the effort and the wait.

Some mention deserves to be made of Dane Laffrey’s ingenious sliding platform set (in a difficult space that is wider than it is deep) and of director Marti Lyons unflinching respect for the script’s daring tone and its wildly original twists and turns.

The cast is uniformly strong, with Von Vogt’s Cuddy something of a revelation (to his Dad as much as to us), as is the calisthenic dance he delivers, Morris or not. But Tierney’s unfazed stoicism and mildly irritated perspective on her situation, illuminates the unselfconscious courage and cynicism of Silverman’s script. Taken all together, Witch delivers a lot of tasty stuff—fun along with more of a punch to the gut than one had bargained for.

Predictably, the devil gets to have the last word. And it won’t be the one you expect.

Across town, at the Greenway Court Theatre, Greenway Arts Alliance and Artists at Play offer another major surprise: an engrossing co-production of the Los Angeles premiere of The Chinese Lady by Lloyd Suh. This performance presents a big change of mood and manner—two actors engaged in a languorous re-enacting of the 1834 historical arrival on the American continent of Afong Moy.

Moy, played here with skill and infinite patience by Amy Shu, was reportedly the first Chinese woman to set foot in the U.S., brought over from what is now Guangzhou to New York City by traders Nathaniel and Frederick Carne. They successfully put her on exhibition as a curiosity gawked at by the masses for much of her adult life, during which she demonstrated her garments, adornments, make-up, eating habits, utensils (chopsticks) and tiny feet, that were kept from growing to normal size by the early childhood Chinese custom of binding.

Other details of her American life are largely missing, though they do include a real meeting with President Andrew Jackson and tours of major American cities. But as the popularity of her show waned, Moy dropped from public view, with speculation that in decline she performed with P.T. Barnum’s circus empire or returned to China or simply vanished in the American horde.

Playwright Suh takes advantage of that scarcity of information to expand on Moy’s difficult acculturation into the American landscape, and how that landscape can distort and potentially kill. It is a quiet lesson in a long overdue subject: the ignored case of immigrant culture shock.

Subtly at first and then more brutally, Suh magnifies the destructive effect of Moy’s personal experience into a broader view of the ravages of objectification. Moy’s opening line, dutifully recited at each performance (of which there were several in a single day), is that she was “brought to America in 1834 when [she] was 14 years old,” followed by the stating of her current age and the ritual demonstration of the actions of her daily routine: how and what she eats, how she walks, what she wears, etc.

It is a repetitive, exercise, sustained—and soiled—over months and then years by the false celebrity it brings her.

In time, the narrowing distance between the carefully painted exterior and the stifling inner reality hollows out not just her life, but her identity—and in a larger sense, as Suh’s script so carefully delineates, it points to the narrowing of the indifferent American soul. The play, if one can even call it that, is an almost static, slow poetic demonstration of the disintegration of rationality, in which the “othering” wreaks complete havoc on the sense of self.

The play becomes a quietly mesmerizing two-character tone poem that plays around with abstract time and sanity, as much with Afong’s as with America’s, in which the tension between her and the devoted Atung takes on some unconventional characteristics.

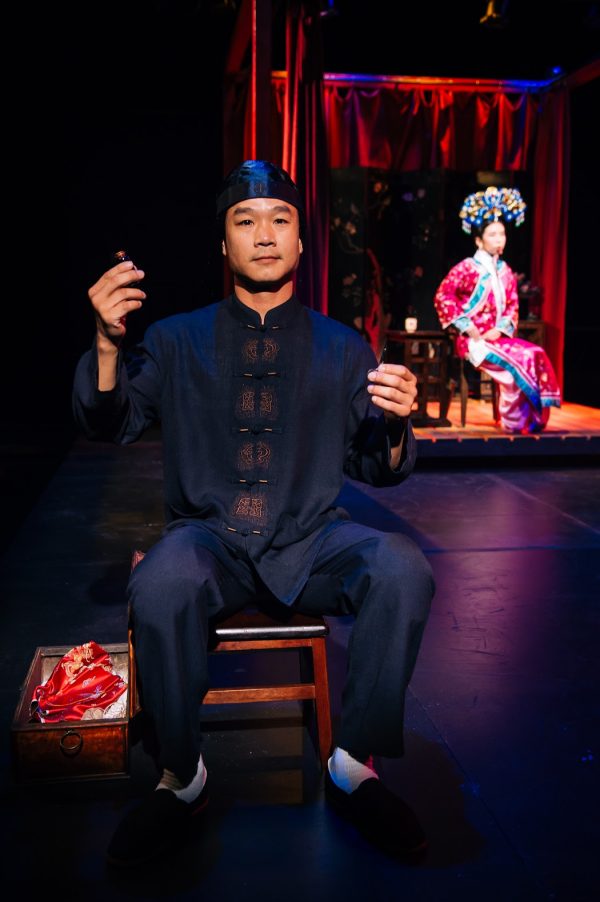

As Moy, Shu demonstrates a patient ability to reincarnate the woman’s almost childlike wonder and obedience to custom, and her insatiable fascination with the fascination that she generates in others, while Trieu Tran delivers an intense, purposeful and penetrating performance as her conscience and keeper as the helper Atung.

Rebecca Wear’s unhurried direction may not be for all markets, but it is exactly the right one for this uncommon material. The production, set on a square empty stage, takes place in a box-like showcase at its center (set and props are by Austin Kottkamp). The historical Chinese and other costumes are the distinguished contributions of designer Hyun Sook Kim and the lighting is by Wesley Charles Chew.

What is so astonishing about this theatrical experience is the delicate manner in which the writer takes his two characters on a meandering journey from anticipation to despair, pointing out exactly how and why it had to happen.

In that respect, the conclusions of Witch and those of The Chinese Lady are nor far apart. Only the road, time, place and styles differ. Not the endgame.

Top image: l-r, Vella Lovell & Huy Iskandar in Witch at The Geffen Playhouse. Photo by Jeff Lorch.

WHAT: Witch

WHERE: Geffen Playhouse, 10886 Le Conte Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90024.

WHEN: Tuesdays-Fridays, 8pm; Saturdays, 3 & 8pm; Sundays, 2 & 7pm. Ends Sept. 29.

HOW: Tickets $30-$130 (subject to change), available at 310.208.5454 or online at www.geffenplayhouse.orgor in person at the Geffen Box Office. Rush tickets available 30 minutes before curtain at the box office, $35 general, $10 students.

PARKING: In adjacent underground lot ($7 ) and on surrounding streets.

RUNNING TIME: Two hours. No intermission.

WHAT: The Chinese Lady

WHERE: Greenway Court Theatre, 544 N. Fairfax Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90036

WHEN: Thursdays-Saturdays, 8pm; Sundays, 4pm. Ends Sept. 29.

HOW: Tickets $34, online at GreenwayCourtTheatre.org or 323.673.0544. Seniors (65+) & students: $25.

PARKING: Free on adjacent campus of Fairfax High School.

RUNNING TIME: One hour 35 minutes. No intermission.