In the recent film The Company Men, long-time corporate employees (played by Ben Affleck and Chris Cooper) are down-sized out of their jobs. After months of self-recrimination and futile attempts at re-training, Affleck’s character finally works through his feelings of worthlessness and figures out how to start a new career, but only after suffering what is (to him) the humiliation of working as a laborer for his contractor brother-in-law.

Chris Cooper’s character, on the other hand, isn’t so lucky. With no prospects, mounting bills and the realization that things aren’t going to get any better for him, he locks himself in his garage, climbs into the family car, and just sits behind the wheel, resigned and calm, as the motor runs and the carbon monoxide slowly billows…

This timely film, written and directed by John Wells, speaks bluntly and forcefully to the devastating problem of unemployment. As the predominant issue of the upcoming 2012 presidential elections, I believe our failed economy–and the staggering jobless numbers that are its starkest indicator—is doing as much damage to the nation’s psyche as to its pocketbook.

I see it every day in my therapy practice—the psychological toll that financial hardship takes on individuals. And it isn’t just pragmatic concerns about paying the mortgage, or putting the kids through college. We Americans have a particularly hard-nosed attitude about work. Prosperity is the result of sustained effort, we believe, a long-term commitment to finding and holding a job. Building a career. Amassing money. Purchasing more consumer goods. Providing the things our families need. Or desire. Or demand.

In the minds of most contemporary Americans, being able to do these things is not merely a sign of success. It’s the determiner of your worth as a person. It means you have succeeded, attained the goals implied in the promise of the American Dream. It is the bulwark against the one unacceptable element of modern life in the West: failure.

(Speaking of failure: The Company Men, which cost $15 million to make, brought in less than $5 million at the box office. It lost money, which, in Hollywood terms, means it failed. Which also means we probably won’t be seeing other films with its sobering point of view anytime soon.)

The plain fact is, never in the past 60 years have so many people willing to work been out of work for such a long period of time. Which means that homes are lost, cars are repossessed, children are removed from schools, and family meals become skimpier and less nutritious. But, as I mentioned above, I believe the psychological impact on the average person is even more insidious.

As is true of most traumatizing events, prolonged unemployment can lead to deep feelings of shame, worthlessness and impotence. When we’re in the grip of such feelings, we tend to place the blame on one of two sources: ourselves (our laziness, stupidity, inadequacy, etc.) or else some imagined “other” (immigrants, foreign competitors, minorities, etc) who has “done” this to us. Regardless of which target we choose as responsible for our dilemma, the result is bad for the nation’s psyche.

Even when it’s abundantly clear that the current economic collapse was the result of Wall Street greed, lack of appropriate regulations, and a decade’s worth of spending that’s created a mountain of federal debt, the average person still labors under the social, familial and cultural myths learned in childhood. In school, at church and in our homes, we’re taught the value of hard work, thrift and enterprise. We’re admonished to “pull ourselves up by our boot-straps” (though, when you think about it, this isn’t even physically possible). We’re told that America is a classless society, and that if you just work hard enough, you can achieve anything you want.

I recall an interview with Bruce Springsteen on the CBS-TV news program 60 Minutes, in which the host praised the singer/songwriter as an example of how hard work and perseverance can lift a lower-middle-class kid to the heights of stardom. To which Springsteen disagreed, claiming that he knew lots of guys who’d worked harder than he had and hadn’t succeeded. As far the Boss was concerned, his career was a result of pure, dumb luck, for which he’d always be grateful.

What a refreshingly candid answer! Because nothing is guaranteed in terms of what the future brings, no matter how dedicated, hard-working, and persistent a person is. And while I agree with golfer Ben Hogan, who once said, “The harder I work, the luckier I get,” it’s still true that circumstances over which we have no control play a large part in how things turn out in life. Just ask any victim of Hurricane Katrina, or any long-term employee whose job has been out-sourced. Just ask any family member of the victims of 9/11.

Yet many of us still cling to the idea that it’s our own laziness, stupidity or failed moral character that is primarily responsible for long-term unemployment. Which is why so many out-of-work Americans drink, gamble and use drugs: for some, it’s the only self-medication they can afford. It’s also why marriages fall apart, business partnerships end, and families fracture: self-loathing can curdle a person, soon turning into ungovernable bitterness and resentment.

Just as it’s almost a truism of American economic philosophy to blame the poor for being poor, many people still adamantly blame the unemployed for being unemployed (which is why there’s little support for creative works, like The Company Men, that say something else). So is it any wonder that many of the newly unemployed themselves fall into this self-recriminating trap?

But there’s another response to the dilemma of joblessness, another position that people sometimes take. For these people, unemployment brings such intolerable feelings of shame and inadequacy that the blame for their situation has to be placed elsewhere. As we’ve seen in times past–and certainly in other nations beside our own–economic stress creates divisions between people. Prolonged joblessness breeds a pervasive xenophobia. We tend to start blaming the “other” for what’s happening to us. Those lazy, unscrupulous, strangely-different “others” who’ve stolen our jobs, wrecked our economy, undermined our way of life.

We all know who these “usual suspects” are: minorities, immigrants, foreign competitors. Nowadays, our divisive political discourse is fueled by such angers and resentments. (And not without due cause: hatred often gets people elected.) And even though minorities and immigrants are as hard hit (or, in most cases, even harder hit) by the current economic down-turn, many people still displace their rage at them.

(Not to mention labor unions, once the backbone of the working man and woman, their shield against the injustices and indignities of an industrialized economy. In recent years they’ve been demonized as well, now seen by a majority of Americans as bloated, corrupt, anti-business, and, somehow, un-American. Amazing.)

Of course, there’s also a great deal of anger at Wall Street and the rich, and with damn good reason. But in my view, since the super-rich live in a world beyond the ken of the rest of us, and have acquired wealth as a result of financial techniques and schemes beyond the understanding of most Americans (myself included, I must say), the extremely wealthy seem to stand above and apart, as if on clouds. They live and thrive in an atmosphere too rarified for most people to really comprehend. Like the ancient gods, they seem to exist on a plane entirely removed from the commonplace.

(Not so removed, however, that many people don’t yearn to join their company, laboring mightily in the hope that someday they too will become rich, famous, special. Believing that some lucky break, like winning the lottery or inventing some new software or selling their little business to some huge conglomerate, will somehow lift them out of their average lives and into the realm of the wealthy.)

Until then, though, the best we can do is hope that some of their celestial riches will “trickle down,” be bestowed on the rest of the population like some kind of grace. Which means the rich and powerful, the global movers and shakers, are ultimately too abstract a target at which to hurl our anger and frustration.

But not so that industrious Hispanic down the street, working for less than any white laborer. Nor that Chinese factory worker, half a world away, willing to put in herculean hours at low pay. Nor that Armenian immigrant who’s just taken over the corner mini-mart. Speaking his broken English in a guttural growl, playing that godawful music. Now there’s an enemy to blame. A villain you can sink your teeth into.

However, regardless of whether we blame ourselves or others for our current economic woes; whether we see the “character flaw” of unemployment as being our own fault or the fault of others, the impact is still the same. Trauma is trauma. And prolonged unemployment, with its resultant lessening of personal and financial power, its unavoidable negative impact on neighborhoods (and neighbors), its insistent attack on one’s sense of efficacy and worth, is a traumatic event.

And what are the symptoms of such trauma, especially in terms of long-term joblessness? Anxiety, depression, despair. A kind of hyper-vigilance about dangers, real or imagined. A growing distrust of others. And, often, a reliance on bitterness and cynicism as defense mechanisms against feelings of impotence and inadequacy. Plus a slow-welling anger at those whom we perceive as “responsible” for our traumatized state.

What we–as a people, as a society–have to realize is that prolonged unemployment is a national disaster, like a flood or an earthquake. That its victims are no more responsible for the havoc that it brings than they’d be for the ravages of a wildfire overtaking their homes. That whether as friends and families, colleagues and neighbors, or politicians and mental health workers, we need to reduce the corrosive effects of blame—either of ourselves or others—and endeavor to provide instead support and solace, both pragmatic and emotional.

How do we accomplish this? We need policies that work, not sound-bites that inflame. We need the humility to understand that large-scale calamities are a part of the life of a nation, just as we need the grit to face the dilemmas squarely and honestly. We need to hold those truly responsible for the economic crisis accountable. Seriously, legally, accountable.

Moreover, we need to understand and accept the interconnected nature of the global financial apparatus in which we are all, each and every one of us, embedded. And to develop and set in motion the mechanisms that will lessen the likelihood of another such world-wide crisis in the future.

Will any of these things happen? I couldn’t say; the answer to that is above my pay grade. But whatever we do in the coming months and years to address our economic woes, unless we challenge the idea that unemployment is a character flaw, that the “blame” dwells either within ourselves or in some alien, dangerous “other,” we’ll remain divided and disheartened. Traumatized by long-entrenched beliefs.

And ending up, if only metaphorically, like Chris Cooper’s character, sitting in a car with the engine running, and the garage door locked tight…

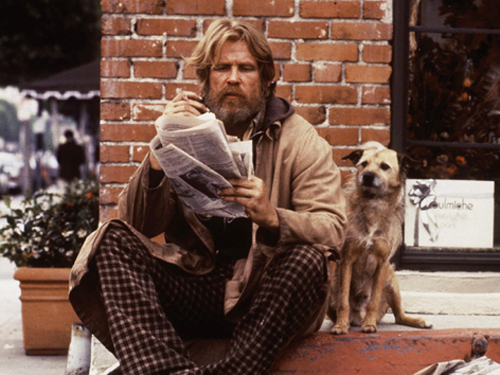

Images of unemployment at the movies, top to bottom: Chris Cooper in The Company Men (2010); Richard Pryor in Blue Collar (1978); Nick Nolte in Down and Out in Beverly Hills (1986), which was a remake Jean Renoir’s Boudu Saved from Downing (1932), starring Michel Simon.