The American art scene in the ’60s and ’70s was almost totally a boys club, and one of the few women who broke through to full membership was Vija Celmins, first in Los Angeles and then in New York.

Now the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art has mounted a full-scale exhibition of her work, “Vija Celmins: To Fix the Image in Memory,” and it’s elegant, instructive and sometimes baffling. Featuring more than 140 works, it’s her first big retrospective in a quarter-century. The roughly chronological sections start with early Pop-influenced works and then move to her trademark contemplative pencil drawings.

Born in Latvia, a child refugee during World War II, Celmins came to the United States with her family in the 1950s and settled in Indianapolis. She studied art at the University of Indiana and by the 1960s was a graduate student at UCLA. She then set up a studio in the beachside neighborhood of Venice and began a 50-year-plus career as an artist, moving to New York in 1981.

Her early work in Los Angeles focused on ordinary objects, things she saw in her studio like pencils and erasers, an electric space heater, a pair of gooseneck lamps. The paintings are deadpan images of everyday stuff, a bit like work by Pop artists such as Andy Warhol and Ed Ruscha, though Celmins employed a more muted range of colors and a slight blurriness in the depiction of things. The sculptures remind you of Claes Oldenburg. Household objects are increased enormously in scale and meticulously crafted, like a Pink Pearl eraser the size of a side table, or a tortoiseshell-colored comb that’s over 6 feet tall.

Some of the early paintings also show a darker sensibility, including a doll house with the second floor and roof engulfed in flames (top image), a bare arm and hand jutting into the picture and shooting a pistol, a gray World War II-era bomber plane in a crash-landing.

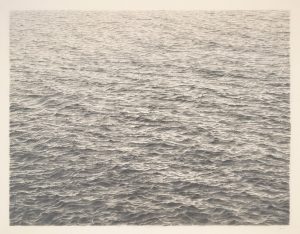

As early as 1968 Celmins started making her iconic pencil drawings based on photographs of ocean waves. These carefully controlled, almost obsessive images — each contains thousands upon thousands of tiny pencil strokes, with no erasures — have a meditative, Zen-like quality. They were followed later in the 1970s by similar painstaking renderings of stones on a desert floor, the surface of the moon, stars in the night sky, spider webs.

More recently Celmins has returned to sculpture, with echoes of Dada, such as a toy globe hanging on a string from a thin wooden flagpole, or a pistol sitting on an old wooden table.

Each of these main themes gets its own gallery in the SFMOMA show. And for most viewers, while looking closely at two or three of Celmins’s ocean-wave drawings is rewarding, trying to take in a roomful of them almost seems to undercut the experience. Still, the astonishing level of craftsmanship in these drawings, the lovely gray tactile surfaces of rocks on sand, of craters on the moon, is not to be missed.

“Vija Celmins: To Fix the Image in Memory” runs through March 31 at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 151 Third Street, San Francisco. The exhibition will be on view at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto from May 4 through August 4, and at the Met Breuer in New York from September 24 through January 12, 2020. An extensive catalog is published by SFMOMA and Yale University Press.

Top image: Vija Celmins, House #2, 1965, wood, cardboard and oil paint, private collection, (c) Vija Celmins; photo courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery.

Sea Ranch Show Spotlights Design That Still Works

Another new show at SFMOMA, “The Sea Ranch: Architecture, Environment, and Idealism,” presents an entirely different vision of California arts in the 1960s. A community of several hundred modernist houses overlooking the Pacific in Sonoma County, about 100 miles north of San Francisco, Sea Ranch is what you get when you combine the Bauhaus’s emphasis on clarity and simplicity with the crunchy-granola sensibility of the hippie and environmental movements.

The site, 10 miles long and a mile wide, was purchased in 1963 by Castle & Cooke and developed under the management of Al Boeky. The master plan was laid out by landscape architect Lawrence Halprin, who set a series of rules that emphasized nature over built structures, modest-sized houses rather than luxury mansions, common spaces more than individual properties. (Halprin had lived in a kibbutz in Israel when he was a young man, and that experience undoubtedly influenced his communal approach at Sea Ranch.)

The houses and community structures were designed by Bay Area architects including Joseph Esherick, Charles Moore and William Turnbull. The distinctive look of the homes, mostly for weekend use, came from their simple geometric shapes and slanted shed roofs. They were clad with weathering redwood siding or shingles — no stucco allowed — and clustered together to minimize their impact on the natural environment. The overall effect reminds you a bit of an Italian hill town, with the structures blending into the landscape.

The exhibition includes architectural drawings and sketches, photographs, four models showing the siting of houses, a 12-minute documentary film, and a full-scale, walk-in model of part of one house, complete with kitchen, upstairs sleeping loft and a living room with wrap-around picture windows that look out to a mural of the rugged Pacific coastline. It’s a terrific way to show both the overall massing and small construction details of the architecture.

It’s also the highlight of a serious, understated exhibition that rewards a close look at the materials on display. Unlike the brutalist concrete architecture that was also in vogue in the 1960s — from the much loathed Boston City Hall to the clunky Embarcadero Center towers in San Francisco — Sea Ranch represents an approach that still feels modern, modest, and human-scaled.

“The Sea Ranch: Architecture, Environment, and Idealism” runs through April 28 at SFMOMA. A catalog is published by SFMOMA and DelMonico Books-Prestel.