In the age of LGBTQ, the tragedy of Oscar Wilde is never far from our consciousness. Laws today may be more enlightened, yet homosexuality seems forever close to the negative spotlight. David Hare, a playwright who has dealt successfully with many complex subjects, tackles the tale of Wilde’s societal downfall in his 1998 play The Judas Kiss, now at Pasadena’s Boston Court, with something of his protagonist’s quick wit. Unwisely, though, it also extends beyond Wilde’s own tendency to be wordy.

The play received mixed reviews when it premiered in London and had the misfortune to open in New York at about the same time as Moïses Kaufman’s Gross Indecency, another piece about Wilde’s ordeal. It was received with more enthusiasm.

Judas Kiss’ checkered production history is not accidental. The playwright made some decisions that stand in its way. It opens with a scene that intentionally misguides the audience. That may be a minor blip in the scheme of things, and it’s a somewhat humorous scene in a play that can use a little more humor (as opposed to wit). But was that scene necessary or a distraction? It chiefly serves to employ a few more actors and delay the real, start of the play. Or the start of the real play. Choose one.

We can forgive Wilde, who suffered deeply for his unbridled infatuation with the heartless and mindless young Lord Alfred Douglas, known as Bosie (a suitably decadent and unfeeling Colin Bates) more than we can forgive Hare. An engrossing writer at his best, this was a curious choice. The same may be said of director Michael Michetti, whose most valuable asset is Rob Nagle, the splendid actor chosen to play the tragic central role.

Nagle, in every respect and in every scene, is a taut and anguished, intelligent yet flawed and ultimately self-destructing Oscar Wilde. As seen in the play’s first act, before his devastating encounter with implacable British law and Reading Jail, Wilde was a writer and a gentleman of stature—in today’s terms, “a star”—suddenly trapped by the jaws of unraveling panic. He is accused of sodomy in a nation that does not tolerate it, and he is still, at least in the play, desperately in love with the narcissistic object of his affection.

When we see him again in Act II, it is in the twilight of his life and in a somewhat undeclared metaphysical realm. The trials are over, the jail time finished, Wilde is in exile and a man utterly undone. We find him in decline, facing poverty, glued to his chair in a sordid Neapolitan hotel. He is by now reduced to accepting Bosie’s charity and his humiliations, just for the favor of remaining at his side to secure food and drink.

British society’s repudiation of a man who once was the center of its collective attention is absolute, but also requires him to endure Bosie’s callous flaunting of some younger lovers. Lover du jour is a striking young Italian fisherman (mysteriously—by directorial fiat?—performed by a lissome Kurt Kanazawa).

It is an unexplained bit of nontraditional casting that is less puzzling than events that follow. Not only does Wilde not leave his seat in Act II until the play’s final moments, he also does a good deal of talking. Lengthy conversations take place with Bosie and Galileo (the fisherman’s improbable name), but also with the sudden re-appearance of Robbie (a neutral Darius de La Cruz), a former lover of Oscar’s whose devotion almost matches Oscar’s devotion to Bosie.

Robbie’s visit is a last ditch effort to get Oscar to save himself by leaving Bosie—a choice Oscar refuses to make. When Robbie departs and the lonely night grows lonelier, and Bosie returns late and alone, the former lovers exchange confidences and recriminations that go in only one direction. The playwright chooses to have this exchange take place in nearly total darkness, by the light of some very dim candles. Michetti has honored that instruction. Among its other flaws, this play is uncommonly self-indulgent.

If this darkness works for the actors, it doesn’t do much for the audience. This is where the play, which up to now never had a particularly well-defined path, ceases to surprise in a rambling, semi-philosophical exchange in which Bosie justifies his craven behavior to Oscar and then leaves, slamming the door behind him.

At this juncture, the back wall of the theatre becomes the otherworldly portal to a final release. The darkness dissipates and dawn arrives on little cat feet. It is the eternity that the now fully abandoned Oscar is ready to embrace.

Se Hyun Oh is listed as the set designer, although it is more a matter of the placement of furniture on a bare stage—bare enough and high-ceilinged enough to play tricks with the bouncing acoustics, depending on who’s speaking and when. Nagle and Bates have no problems being heard, until it comes to that confessional in the dark.

Dianne K. Graebner’s costumes are a highlight of the production, and the lighting by David Hernandez is fine except for that crucial stretch of obscurity in Act II, but still. It needed to be handled in a way that allows the actors’ faces to be seen; listening gets harder when you can’t focus on the speaker.

Michetti’s light hand is usually more discernable than it is here, perhaps out of a desire to honor the author’s wishes. Sometimes, finding a middle ground is best.

Top image: l-r, Colin Bates, Rob Nagle & Darius De La Cruz in The Judas Kissat The Theatre @ Boston Court.

Photos by Jenny Graham

WHAT: The Judas Kiss

WHERE: Boston Court, 79 No. Mentor Ave., Pasadena, CA 91106.

WHEN: Thursdays-Saturdays, 8pm; Sundays, 2pm; Monday, 3/18 only, 8pm. Ends 3/24.

HOW: Tickets, $20-$39, available at 626.683.6801.

PARKING: Free, in a lot behind the theatre.

RUNNING TIME: 2 hours, 40 minutes, with an intermission.

***

AND ON TO…

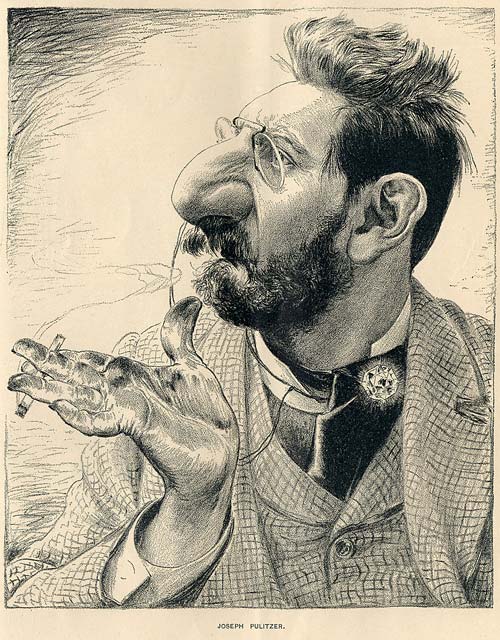

Joseph Pulitzer: Voice of the People, a documentary feature that opens tomorrow, March 8, in Los Angeles theatres, is a surprising reminder of how much modern journalism owes to this man. We know Pulitzer today primarily through the Pulitzer Prizes, but we don’t necessarily remember what he did, much more significantly, for the rise of excellence in journalism when he was running The St. Louis Post-Dispatch and New York’s rough-and=tumble The World. It’s even easier to forget that this Jewish immigrant from Hungary came to America and to newspapers with no English and no prior experience in journalism, which also may explain why he felt so free to almost re-invent it.

The story goes that the German-speaking Pulitzer taught himself English by reading Charles Dickens (claimed as his favorite writer). He also learned journalism on the job, when he sold an article to, and then went to work for, the St. Louis’ German-language Westliche Post. Eventually, Pulitzer bought the Post and, after his later purchase of the St. Louis Dispatch, combined the two and established the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, which exists to this day.

Many of Pulitzer’s singular achievements are touched upon, if not deeply examined, in this 85-minute documentary feature directed by Oren Rudavsky who, with others, also wrote and produced it. But the main focus of the film, aided by commentary from scholars familiar with Pulitzer’s story, is on his difficult and complicated personality and his uncompromising work ethic, and how the combination of the two led to the creation of today’s version of journalism, with its insistence on a free press.

These characteristics also were responsible for Pulitzer’s meteoric rise in the newspaper business, one that he essentially helped mould by recognizing and responding to what he saw as public demand. He did things that had never been done before. He wrote about sports, published the names of tax dodgers, zeroed in on titillating sex and crime stories, served the practical interests of his readers, by doing such things as including patterns for high fashion styles that would enable lower income women to make their own fancy dresses if they wanted to.

He had a knack for sensing what people wanted and instinctually made choices that encouraged people buy newspapers daily — sometimes more than once, by printing various editions throughout the day.

Journalism, now the center of his life, brought him wealth, rivals and enemies, many of them in high places. Theodore Roosevelt called for “vilifying” him after The World exposed an illegal payment of $40,000,000 made by the US to the Panama Canal Company. A nasty rivalry with William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal in the 1890s, only led to increased sales and the birth of “yellow journalism,” stepping up the interest and growing importance of journalism in general.

Rudavsky hits most of the important notes in this documentary, which should be of interest to anyone concerned with the significance of the role of the press in the political health of any country, to say nothing of some implicit parallels with today’s politics. Rudavsky focuses as much on journalism’s grubby yet spectacular rise under Pulitzer as he does on the man’s hyper-intense personality: the difficult temperament, frequent depressions, other physical afflictions, and almost fanatical emphasis on accurate reporting free of interference. No fake news.

The Pulitzer Prizes — established in 1917, after he was gone, but thanks to his endowment to Columbia University — may be how we remember Joseph Pulitzer today. But it is the fundamentals of journalism that he developed and the Columbia School of Journalism that his money funded in 1912, one year after his death, that are by far what fascinate and matter most.

Joseph Pulitzer: Voice of the People will play at various Laemmle Theatres in the Los Angeles area beginning March 8. Find more information here: https://www.laemmle.com/films/45409