“Every time I read Baudrillard’s dictum to Ecclesiastes I think,

‘Here is a man who prefers talking dirty to fucking.’”

Bushwick (2009), journal entry on the Semiotext(e) edition

of Simulations and Simulacra printed en los Sures de Williamsburg

And how many times have we heard that line do you think

I’m blind to trade my mind for what you call fine

Never in my time I’m not in your movie

Bad Brains, “At the Movies”

*

In the late 1970s, North Brooklyn community development and non-profit organizations, civic associations and related social groups employed professionals, contractors, and laborers increasingly identifying as ‘white artists.’ ‘High rent elsewhere,’ typically ‘rent too damn high in 1980s and 1990s Manhattan’s Lower East Side,’ is only one reason the white artists came to Williamsburg. For all the self-identifying creativity, it’s astonishing that white artist explanations for ‘why we moved t/here’ are so unimaginative, uniform and reductive, so unheroic, as if arbitrarily denying even concealing other factors, such as sweat equity bargaining. The reasoning may have been valid once but certainly not now—who in the present claims to move to Williamsburg because it’s affordable? But more importantly, how valid has it ever been? This group has repeatedly identified itself as ‘harbingers,’ ‘discoverers,’ ‘pioneers’ and ‘bootstrappers,’ the very ‘vanguard of gentrification.’

The power of such terms is self-evident. Indeed, one can smell a whiff of the sexual and macho whenever hearing artists describe themselves in North Brooklyn. And yet, that seeming power and agency is neutralized every single time white artists explain how they first got to Williamsburg—on the contrary, we are told, the artists were powerless. Market forces compelled them. The rent was too damn high in the Lower East Side. There was nothing they could do. And ’til the present, they somehow are omnipotent in every regard while impotent before gentrification. It bears an uncanny similarity to the adventures of Christopher Columbus, brave commander of ships over the Atlantic Ocean but ‘lost’ and only ‘accidentally’ discovering the so-called ‘New World.’ Given the paradigmatic status I assign to gentrification, I’m often asked if anyone exists I do not consider agented when I think the appropriate question, having heard all these explanations on how artists find themselves in Williamsburg, is whether anyone has agency.

It bears emphasizing they identified and were in turn identified as white artists and white bohemians, sensitive, perhaps, to Art existing in Williamsburg beforehand, thus requiring distinction. Curiously, however, they were multicultural, if not international, sharply contrasting the stereotype of today’s actor in Williamsburg’s gentrification, the hipster, as Midwestern-American yearning for a coast.

Race is muted, while politics remain implicit—it’s ‘hipsters,’ not ‘white hipsters.’ They are connected, by a sort of popular genealogy, with ‘artists,’ though both identities precede Williamsburg’s gentrification. But the ‘Williamsburg hipster,’ unlike hipsters in other periods and places, emerged and developed simultaneous to the personal computer and Internet, to neoliberalism’s rise, so had a greater and universalizing impact. As the gentrification ages, these identities grow distinct and apart from each other—supposedly reflecting generational gaps. Early on, ‘artist’ was interchangeable with ‘hipster.’ Now, there are ‘younger’ hipsters and ‘older’ artists, but some connection remains, almost familial, perhaps even incestual, so things remain simple, rational and continuous: artists inspire and hipsters inherit Williamsburg’s gentrification. This is ahistorical. There is little basis for it in fact.

Examining the major ‘art’ and ‘social’ events from the late 1980s to the mid-1990s, especially the Williamsburg Warehouse Events when white artists were most socially active while still ‘alien’ and ‘novel’ to every other demographic, with commercial forces emerging in the Northside, such as the L Café on Bedford Avenue and Test Site Gallery on North 1st Street at this period’s early stages, Sweetwater Cafe at the final stages and Thai Café on Bedford Avenue mid-way, tells us something else entirely. The Williamsburg hipster did not evolve from the neighborhood’s white artists, nor from previous hipster styles and forms such as in central and western Brooklyn. The Williamsburg hipster more directly descends from the so-called ‘traditional’ or ‘trojan’ skinhead. Their awareness and eventual presence in Williamsburg has less to do with the white artists than the final Williamsburg Waterfront Events and their organization by ABC No Rio and related parties when they became the Beer Olympics—the establishment of the Sweetwater Cafe on North 6th Street between Berry Street and Wythe Avenue and of Mugs Ale on the corner of North 10th and Bedford Avenue attest to this.

Recognition of the fact makes it less difficult to understand how today’s Alt-Right is hip. It’s striking how ‘skinny jeans,’ preppie fashions and irony’s conspicuous display, crowned in mod hairstyles, especially among women, along with the music styles now popular in North Brooklyn, could pass in twenty or so years without anyone noticing the blatant similarities between ‘Brooklyn hipsters’ and ‘Manhattan skinheads’ or the more blatant dissimilarities between hipsters and the artists beforehand in Williamsburg. It’s no coincidence that Fred Perry and Doc Marten retail operate on Grand Street in the Southside and Bedford Avenue in the Northside, respectively, at gentrification’s latter stages.

Profound irony of the last 20 years, then, that multitude professional and personal blogs, social media posts, public comments on Internet newsfeeds, and or writings/works, covering the private-public partnerships for the neighborhood parks and the Northside Williamsburg community organizations and events, indeed the actor of gentrification on Bedford Avenue identifying with the creative commerce and tavern economy, mocked New York Times coverage of Williamsburg after the 2005-rezoning that allowed for luxury condominium skyscrapers on the North Brooklyn waterfront. The coverage warrants criticism, but this ridicule has been hip. Indeed, there hasn’t been anything hipper, ever, in Williamsburg, than to taunt someone else for lateness—hipsters are exoteric about being esoteric. It went, basically and usually, that old fogey Gray Lady only covered Williamsburg after leeringly spotting younger hipsters defeating her to the chase, a classic case of institutional appropriation of subversive individuals and places, and this talk of commodification wasn’t egomaniacal at all, suitable for discussion, even decorous for celebration without snickers and eye-rolling, because it was about the erotic alienation of whiteness. For example, Andrew Kalish, for literary blog The Coda, interviewing Kristin Iversen, managing editor of Northside Media Group and feature columnist for Brooklyn Magazine, just three years ago, with my emphasis, “Can you expand a bit on the phrase ‘the whole idea of Brooklyn,’ not to sound like the New York Times coming late to the party, but what is the editorial viewpoint of Brooklyn?” Or Christopher Robbins for Gothamist in 2012, “We’ve been rather hard on the New York Times recently, but it’s almost as if they’re dipping monocles made of melted iPhones in artisanal mayonnaise and flinging them in our faces, daring us to swat them down.” (“NY Times Drops Mother Of All Gentrification Stories On Greenpoint”) ‘Classic’ is the inversion that projects from everyone involved in the neighborhood’s gentrification, because the tardiness and artisanal mayonnaise was their own. Hipsters saw no irony moving into the neighborhood after the new millennium, after the white artists, after the Puerto Ricans, and disparaging others as dilettantes. Or notice any tension between secularism and their identity politics.

[alert type=alert-white ]Please consider making a tax-deductible donation now so we can keep publishing strong creative voices.[/alert]

There’s been no consideration anywhere into religion and identifying as ‘millennial,’ let alone in Williamsburg’s gentrification, a fin-de-siecle. The New York Times preceded Williamsburg’s hipsters by close to twenty years, so we’re talking about almost forty years back when the paper included Williamsburg in a larger Brooklyn zone of ‘art colonies’ (Marcus Brauchli: “Brooklyn Rents Lure Artists” October 1983) and then, three years later, publishing an installment about Williamsburg in a well-known and well-regarded column in its internationally influential Real Estate section, “If You’re Thinking About Living In.” On the contrary, New York Times coverage on Williamsburg’s gentrification precedes Coda, Curbed, Gothamist, L/Brooklyn Magazine, Block Magazine, Undertow, Waterfront Week, Brooklyn Brewery, Williamsburg Walks, the respective and annual Open Studios, even the vaunted Williamsburg Warehouse and Waterfront Events. All of this misrepresentation about the New York Times overcompensates for a lack of charisma, by hipsters perhaps aware, even recoiling, at explanations of “the rent is too damn high in the Lower East Side” by white artists they erroneously and perhaps duplicitly claim inheritance from.

Long before hipsters, early in gentrification, on or around 1979, the earliest actors in gentrification spread word about sweat equity in Williamsburg, and drew colleagues who, with each migration, increasingly removed themselves from area non-profits until bearing little to zero relationship or interaction with those organizations, even less with the underlying houses of worship. Only by this process could the setting be friendly for ‘Art’ in Williamsburg’s gentrification—tzimtzum. The earliest white artists were not religious but ‘spiritual,’ not apolitical but depoliticized. This was possible by sweat equity. For low income tenant associations with adverse possession of in rem properties, charisma legitimized their members and granted them authority to collect rent and hold monies for bills or repairs absent property ownership or state authority. Any neighborhood tenant association can burn the ear with bochinche about its members, but Williamsburg’s many HDFCs testifies to faith and trust between neighbors, enough to invest in uncertain parties and surroundings. That charisma gathers in the community’s houses of worship and projects out of religion. This was immaterial to private and individual owners bargaining sweat equity over in rem or distressed properties—they did not adversely possess but owned or gathered to own properties and did not need nor require charisma to collect rent. State authority and institutional forces presupposed them. Where tenants were ‘artists,’ rent was often not paid in cash, anyway. More important was making repairs and renovation. This made for an interesting neutralization of personality and passion, and the gentrification’s vanilla predicates on this bland nihilism. In fact, Williamsburg’s houses of worship are disappearing and their congregations in decline more radical than can be accounted for by the surrounding population’s displacement. All that personality and passion had to be projected somewhere, even if it meant shevirat ha-kelim, even if it meant shattering relations between the agents of gentrification and Williamsburg’s Puerto Ricans, and that is exactly what has happened with gentrification’s tellings of ‘Williamsburg back in the day’—a projection.

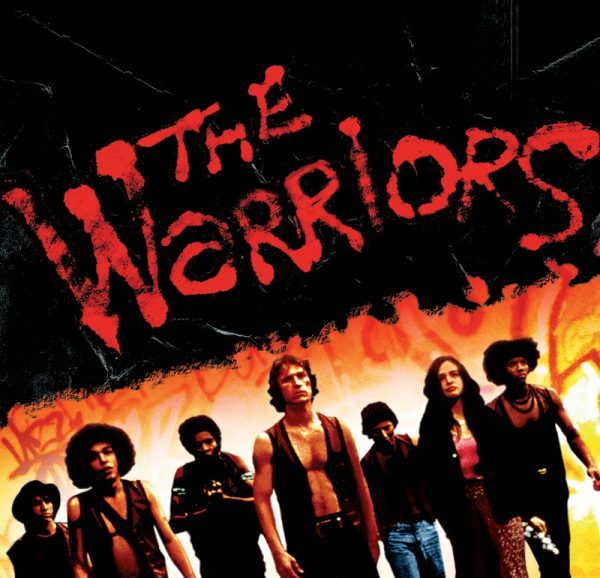

It’s fitting then that The Warriors and Alien played at the Commodore Theater on Rodney Street and Broadway in 1979 as gentrification literally took place. The love that Williamsburg’s Puerto Ricans have for The Warriors is something to behold. Scarface (1983) and The Warriors are two of my brother’s favorite films, and he touts how often he has seen them like Americans tally seeing the first Star Wars trilogy. Like many Puerto Ricans, he even authenticates The Warriors. The most common saying in Williamsburg associated with the film has been, “Back in the day was really like that.” They are often astonished to find that it’s also based on Xenophon’s Anabasis. By the film’s release, the Southside gangs were in steep decline and being replaced by individual drug dealers leading ‘crews,’ but that is less shocking. My generation and my mother’s came out of the Southside gangs. My front door was setting for North Brooklyn’s rumbles. And yet, there is next to nothing I recognize in The Warriors of Williamsburg back in the day. Nay, Williamsburg back in the day’ was more Once Were Warriors (1994) than The Warriors.

Alien is more authentic than The Warriors. It is released to theaters as gentrification begins in Williamsburg, and its prequel, Prometheus, set before but fresher looking, not content with explaining the monster but concerned with Creation’s origins itself, is released in 2012, just as a wave washes over Internet and print media covering Brooklyn, over New York and international real estate coverage, about gentrification’s origins in Williamsburg. In the classic original, a shade of Forbidden Planet (1956) gestates around a man’s heart and births out his chest, rapes and murders a crew on a colonial ‘claims-making’ mission, but spares the cat. The genius of the Ridley Scott arc of the Alien/s canon, hallowed and definitive, is that only so thoroughly secularized, modernized and remote a representation to religion could vitalize such a strange, sexual and satanic creature. In the years that follow, the nation is swept up in satanic ritual hysteria—the alleged abuse, abduction and murder denominated by sex and not much, if any, substantiated by federal authorities after prolonged investigation—a public imagination. What is substantiated was the concealment of widespread child abuse by all the claimants and storytellers of demonic characters. Presently, artists from the Greenpoint waterfront advocate for a feral cat colony’s protection from nearby construction for Greenpoint Landing, but we digress?

After the 2005-rezoning, many neighbors noticed the intensifying sexuality in real estate advertising for Williamsburg, but no one has cared or dared to speak on sex and sexuality in the gentrification, though doubtless there’s been action from the get-go. More than civics, or the tavern economy, non-profit organizations and activist circles, or educational institutions, the primary interaction and communication between actors in gentrification and the Puerto Ricans has been and continues to be and will always be sex. That activity charts, again, from religion, from area houses of worship and through civics and non-profit community organizations where actors in gentrification relate to Puerto Ricans, by charisma. The silence about it contrasts the activity. All that repression is projected into a perfect dark-skinned organism with bloated head and tail, indeed this monster is an anthropomorphization of cock and pussy, a collage of sexual organs walking upright, ‘discovered’ on some blighted rock by claimants diverting themselves through derelict structures. The monster is charismatic, lustful and murderous, but it’s not indigenous to the location of its discovery. Indeed, it’s not indigenous anywhere. It is ‘found t/here’ not ‘from t/here.’ Williamsburg’s Puerto Ricans continue to strongly identify with The Warriors, but it makes more sense, given the gentrification, we understand the identification with Alien, since the Supreme Court has ruled in the so-called ‘Insular Cases’ that we are an ‘alien race,’ and the demonic, or rather, demonized ‘sexual other’ fit white artist projections of and overcompensations for ‘Williamsburg back in the day.’

Williamsburg’s white artists would be noticed first by Prospect Heights Press in 1980, but the neighborhood’s first self-conscious ‘art group’ forms in the Southside, WACCY—founded by Frances Lucerna. She and other principals would later establish celebrated school El Puente on 211 South 4th Street on the Roebling corner. Though its Puerto Ricanness apparently prevents its mention in historical tallies of Art in Williamsburg, WACCY is apparently a vanguard as well —Menudo hysteria sweeps the Diaspora and my sister, cousin and friends end up in dance groups rehearsing in the upstairs theater at St. Paul’s Lutheran Church on Rodney Street and South 5th Street and near the Commodore Theater (where my friend Angel Reyes entertained us performing with San German). We move to a fourth floor railroad apartment at 63 TenEyck Street, near a sprawling ‘abandoned’ lot along Lorimer Street between TenEyck Street and Scholes Street with Stagg Street barely crossable through its middle by automobile—piled with soil, rubble and the homeless that the neighbors dubbed ‘las Montañas.’ Over the Williamsburg Bridge, punk rock and new wave are giving way to New York Hardcore, and skinheads who are ethnic and multicultural but also far-rightist and white supremacist venture east down St. Mark’s Place to Avenue A. Later, gay-bashing by skinheads sweeps across Lower Manhattan and the police riot in Tompkins Square Park to ‘clear squatters.’

This is part 4 of a 5-part series, T/Here in Williamsburg, that explores the history of gentrification in the Southside of Williamsburg, 1968-1982, through personal and historical narrative. Part 1, 2, 3.