they shook their heads

when we started fighting

amongst ourselves

the clouds of acrid smoke

and the sound of gunfire

floated over the razored wire

wall and that invisible line

in the dirt we once

patrolled diligently

with flying drones and

neo-Nazi patriots

(from “the road taken”)

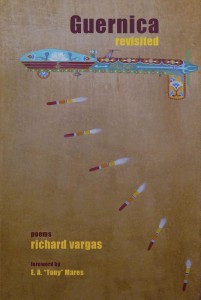

It’s easy to miss the voice, but you do so at your own risk. It doesn’t shout. Richard Vargas has a deft touch. There’s a quietness in the voice, an immaculate control of tone and, still more rare, a wryness of observation as if the poet had stared death in the face and seen through its many guises like the engravings of José Guadalupe Posada. Guernica revisited (Press 53, 2014), Vargas’ third book, ends with a laugh.

Between its pages, Vargas bears witness to anti-immigrant xenophobia where even Superman is suspected as an illegal alien, the outrages of war and the trauma of unemployment. This sociopolitical commitment is balanced and leavened by carnal delight and an attentive eye for natural wonder.

“song for Shenandoah” is a magnificent poem-series, a folk epic, a lament:

we climb your walls and

wade through muddy brown river

we walk and run across deserts

hide in bushes and seek shade

while drinking warm water from

discarded plastic Coke bottles

tied to our waists with twine.

It tells the history of a strip mined town, its industrial rusting and its need for “new blood.” The poem describes the harrowing migration through borderlands for “the jobs you / don’t want,” the arduous labor of Mexican workers, the counter-hate and its tragic consequence:

a religious medal hanging from

the neck and stomped into a man’s

chest will imprint the holy face

of the savior deep into the skin.

Section V. details the terrible etymology of a word:

wetback

is the humiliation of

tired and hungry ancestors

enduring its ugly sound

while picking Texas cotton

and California grapes from

swamp to sundown.

But like the original 19th century shanty, which was also associated with runaway slaves, “song for Shenandoah” is a story of “coming home.” It’s about staking a claim and planting roots in el norte.

What makes these poems seem deceptively simple are the short lines, the columnar shape of the poems, a handful of prose poems. Their modesty is marked by an almost total absence of capitalization, that’s to say, an equalizing of the alphabet which proves again the only true democracy in America is the arts.

But Vargas earns such simplicity through a conversational ease that can be a difficult thing to pull off, since it’s without pretension, shorn of rhetoric and ornamentation. “A poem is a naked person,” Bob Dylan once said.

There’s a sprinkling of Spanish in this collection, but not a lot. Vargas’ language isn’t the calo (Spanglish) of pioneers of Chicano poetry like Alurista and José Montoya. He comes from a later generation. It doesn’t matter. There’s plenty of linguistic space in this country. Often, the poetry has a lovely, reverential quality that is profoundly spiritual—milagros, es verdad?—a mordant humor and a love of the corporeal that knows both sin and sacrament.

The poet’s knowingness about relations between women and men is wise in an image-world of misogyny, as witnessed in the recent mass shooting in Isla Vista. “women and guns” is a self-explanatory title, but Vargas’ association with females who pack heat is handled lightly. After telling his ex about the “crazy women” he’s been dating, she tells him “it’s good for you I didn’t have one.” This is a little like Joan Didion saying that when the Santa Anas blow, wives measure their husbands’ throats for the knife. The poem ends with a noirish fade to black:

I hang up feeling like my luck

is about to run out.

There is a wonderful series of epiphanic milagros too. This from “milagro #3”:

neighbors celebrating

Passover with solemn

songs of long ago

when a bloodied

door kept the angel

of death at bay.

Among the most personal and powerful poems are a series documenting the humiliations of unemployment. In “the company provides free lunch on the day it lays off 250 employees,” the officious rituals of separation are described along with the attendant shame:

some hold on to their boxes as

if they are naked and are

trying to hide their genitals.

Vargas recounts the security oaths in place in corporate America. He itemizes the lunch menu. The stark specificity is absolutely devastating, like “a tub of butter substitute.” The poem ends with “one can of soda / (off brand).” Behind the quietness of the poem is Vargas’ knowledge that in the U.S. there are no ceremonies of grief or parting when it comes to layoff, no treatment for post-traumatic stress that can accompany going on the dole. It’s purely awful.

The penultimate poem in the collection, “funeral song,” prophesies his own demise with remarkable humility:

now my time is up

just let me step aside

vacate this space

so someone else

can take my place.

It should be said Vargas comes straight outta Compton. Sans obscenity, he came up on the same sun-blinded streets as Raymond Chandler, Marilyn Monroe and N.W.A.

Vargas is no stranger to American violence or the palpitations of Hollywood. In fact, he’s in love with those big-screen, archetypal images of sex and heroism even as he honors the working folk that labor in the shadow of the Dream Factory. Vargas knows not only the City of Angels; he knows the City of Devils, too.

Image: El famoso cuadro Guernica de Picasso, símbolo del horror, pintado sobre las Hayas del Monte Alduide en Zilbeti. Photo by Ketari. Under creative commons license.