In 19th century portraiture there was a fascination in photography (and

to a lesser degree in painting) with backgrounds littered with relics and

décor that were suggestive of the ‘Orient,’ the colonized world, the

‘other.’ These trappings served several purposes. They reinforced the

mastery of white Europe, but they also, less consciously, fetishized

distance, and the distant. It was one of the beginnings of commodifying

the exotic, even as it established its parameters. One might trace these

background trappings as they morphed into picture postcards, and

other tourist souvenirs.

that part of what post modernism is about is the recognition that the

ironic has exhausted the subject. This really began around the time film

was invented. It has run straight through the 20th century and into our

current century. The bourgeois subject in those 19th century

photographs was teetering on the edge of public immersion in the

spectacle.

The latency that Durer portrayed in his famous Melencolia engraving

(1514) posited signs of a hidden knowledge, or mysteries, that the

concentrating angel was trying to decode. The angel was paralyzed with

this effort. This was an allegory about the emancipatory dimension

promised by rational thought. That model has lived on for several

hundred years. That latency was to later be channeled into marketing.

And in marketing exhaust itself.

Lars Von Trier’s recent film Melancholia runs up against this

exhaustion, but sadly the filmmaker seems not to know it. There are a

number of comparisons to be made with the Von Trier; firstly Buñuel’s

Exterminating Angel. The formal dinner party in the Buñuel is used to

point to the margins those rich guests seem unable to know or

understand. Their prison is their own class, and its blindness to the

world outside. Antonioni’s Red Desert is another film that has a related

cinematic DNA. But again, as Antonioni was at least nominally a Marxist,

his heroine, amid the factories, seems to bring the viewer’s attention to

her search for context. The exhaustion I speak of, has led narrative into

a genre cul de sac (or cul de sac of genre). Everything is genre. You can’t

escape it. The problem with Von Trier’s film is that it’s a science fiction

movie pretending to be without a genre context.

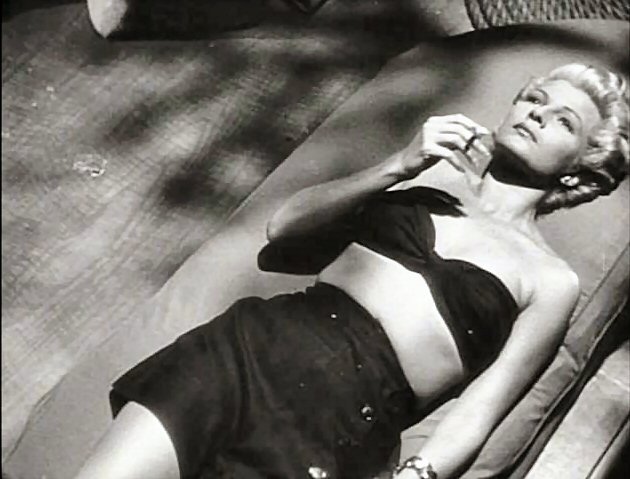

There is a shot of Kirstin Dunst, naked, staring up at the approaching

planet. It is an homage to Welles’ shot of Rita Hayworth in The Lady From

Shanghai. Why is it such a pale imitation? One answer is that Welles

knew the film he was making. A crime movie.

The guests in the Buñuel are critiqued. The guests in Melancholia are

critiqued, but in the way the police are “critiqued” in TV cop shows. The

result of Von Trier’s lack of understanding of the historical moment he

exists in, results in the utter emptiness of the planet’s moment of

collision. What happens? Well, the earth explodes sort of. That’s it. The

metaphoric and allegorical import along with it. I was reminded of

Danny Boyle’s sci fi film Sunshine, in which the director’s vision

extended no further than imagining the galaxy as a screening room for

dailies. All that could be found of life left at the far reaches of space was

to shoot it out of focus. Then sit in the dark and screen it. The same

insufficiency plagues Von Trier. A cast of “prestige” actors, the better to

make sure this WASN’T mistaken for a fucked up installment of Star

Trek, are left to complain, in their tuxedos, and gowns, while the story

wanders the film much as Dunst does the mansion.

So from Durer to Von Trier, we have gone from the religious to the

political to pure commerce. The reality of narrative in cinema today is

that unless there is a stripping away of bourgeois melodrama, as one

can see in a variety of recent film (Escalante’s Los Bastardos, Audiard’s

A Prophet, Lynne Ramsay’s recent We Need to Talk About Kevin, or in

the Australian cinema of Animal Kingdom, Little Fish, and Noise) the

recognition of primal crime has revealed the core fascination this

culture has for that narrative form. The criminal, a Lacanian criminal if

you will, driven by primordial rivalry and aggression. It is our

postmodern Sophoclean moment. The split that kept Hegel so

frustrated, between art and life, is now realized as the very nature of

consciousness as we suffer it.

The empty formalism of Von Trier seems a watery apology in the presence of Escalante’s undocumented workers,

or Audiard’s Algerian petty thief. Or the recovering junkie in Little Fish.

Or the disturbed child of a bourgeois couple in Lynne Ramsay’s flawed,

but perhaps profound We Need to Talk About Kevin. For Kevin is alive

in his crimes, and he resonates as Raskolnikov did for the 19th century.

Justine and Claire, the neurotic priviliged sisters of Melancholia only live

in simulacra of reality – a world of paternalistic derangement, but one

they (and the filmmaker) are unable to break free from. Von Trier’s film

seems most to be about impotence, if it’s not about autism. I had a

similar reaction to McQueen’s overwrought melodrama, Shame. Again, it

is a bourgeois expression of angst. Again, the formalism is empty. Again,

the protagonist is clueless as to his own privilege and the world of

suffering he inhabits. There is something comforting in the Von Trier

film, since , you know, there really ISN’T a planet about to hit earth. So,

we can all return to our private stables and personal wine cellar and our

BMWs. The help is invisible in Melancholia. The workers, the

groundskeepers. They are never seen. It’s a bit like Sophie Coppola’s

gloss on the Court of Versailles. Those darned mobs are ruining my

parties. When they appear, we never see their faces, only the back of

their heads.

The planet Melancholia arrives as empty metaphor. The moon over

Rita Hayworth passes through a night of mystical desire, as the boat

sails toward the American shadow‐land, Mexico. The spectre of colonial

thinking is almost impossible to avoid, regardless of what film you

make. Its absence is a presence, and it speaks directly to that Lacanian

portal into the symbolic. The most direct way out of the imaginary is

through criminality. The sons have become the father; they inherit his

crime. German Romantics saw a tragic version of this; of responsibility

and guilt. However our identity links up with the formation of our super

ego, however one charts our primary narrative fiction, the post modern

aesthetic is a reduction of elements in narrative, and that somehow the

lack we feel in the ‘other,’ that fundamental psychic trauma, renders us

immigrants or criminals or both. It is the most basic of artistic failures in

this historical epoch. Lacan observed in his essay on Hamlet, that ghosts

appear “when someone’s departure from this life has not been

accompanied by the rites that it calls for.” Hamlet’s father is dead, but he

returns. He returns as the repressed, and more significantly as part of a

system of signifiers; “the hole in the real that results from loss sets the

signifier in motion.” Myth and allegory provide us with the structures

by which we navigate our desire and our rage. The allegorical, however,

only resonates when we know our own complicity in the crime.

McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men (book not the film) is a meditation

on this complicity. Audiard’s A Prophet is the same. Claire Denis’ Beau

Travail is the same (based on the Melville novella Billy Budd, perhaps

the quintessential example). At the heart of it, the murdered sleep of

Macbeth returns. Films that examine privilege must cleave closely to

the irrational in this, our, system of progressive rationalization. Ang

Lee’s Ice Storm comes to mind. Privilege lives too intimately with the

very economics of filmmaking, so that a willful blindness occurs. In

some sense, in some related way, probably all films are about

filmmaking. All narratives are about crime. The unconscious today is a

film strip – if Beller is correct – and it screens that which pleads for

mercy, pre‐emptively, for we all know for what we will be arrested. The

religious symbols in the Durer engraving, or in the background of those

19th century portraits, are now scattered across super market tabloids.

That latent meaning that resided within structures of ritual and

allegory, now only serves as distraction – purposely trivial, harmless.

The refuge of “prestige” projects is that they announce their seriousness

through various signifiers (classical music, in this case Wagner…which,

as I think on it, is almost self parody) and through these devices, they

escape historical and social context. Melancholia happens nowhere. Or

anywhere, or everywhere. But its without context (as Kevin says, in the

Ramsay film, “I AM the context!”). The forgetting of history as it is

written in artistic forms, in the ruins of past cultural product, is to

practice from a foundation of false naïveté, and to undermine the

allegorical.

The Enlightenment has run its course and film, as the predominant art

from of our culture, embodies all the contradictions of late capital, social

domination, and the spectacle, and is therefore a medium that fails if it

forgets its allegorical beginnings along the seashore, an amusement

park novelty. Adorno said even in Shoenberg, the distant echo of the

café fiddler could be heard. Von Trier is pretending he can’t hear the

waves, or smell the salt water taffy, and maybe he really can’t.

Images, from top: Melancholia (Von Trier), Melancholia (Durer), Melancholia (Von Trier), The Lady from Shanghai, Los Bastardos, We Need to Talk About Kevin.